Chapter One

Principles and Promise

I’m a verbose communicator. My coworkers started creating flashcards of terms I introduce to them. Like bifurcate, precipitous, or germane. So you can imagine my excitement when I learned of The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows by John Koenig,1 within which he coins new English terms for emotions we feel, yet have no words for. John defines one such word2:

sonder: noun. the realization that each random passerby is living life as vivid and complex as your own

This was open source for me, and it might be for you too, now that you’re reading this book. I remember peeking into my first project, observing whole histories already played out, planned, and performing in real time. Little subcultures of loosely-aligned folks working together. It was all a bit over my head…but I did have a new perspective leaving that place. Once you attune your ears and eyeballs, it’s hard to miss. Open source software is more than a license. Far more than free code. Open source software is code plus community. It’s a vibrancy and a sprawl and a fulcrum and a tool and a burden and a beacon. And it needs you.

Communities whir along unseen, yet shape the products we use, the news we hear, the jobs we apply for, or the conversations we have with loved ones. Open source is all around us, omnipresent in our digital, professional, and personal lives. You’d be hard-pressed to find software that doesn’t lean on open source somewhere in its composition, design, or delivery. It’s a medium in and of itself. It’s the tug-of-war rope via which ideological, economic, and cultural contests play out. Open source is a mirror, projecting whatever predispositions we wish onto the moment.

You already contribute to the open source ecosystem—you just might not see it that way yet. First and foremost you participate as a consumer, as a user of things. You browse and build websites atop open source software. You read documentation. You visit the repository of a project your team uses as a dependency. And so does everyone else. The company you work for, the school you attend, the businesses you visit—they run on open source software.

The Linux Foundation estimates that 90% of production software is of open source origin.3 Researchers at Harvard Business School calculated the total demand-side value of open source at 8.8 trillion dollars.4 It’s nearly unfathomable in its scope. I think Oscar Wilde was bullish on open source way back in 1892 when he wrote this dialog for Lady Windermere’s Fan5:

Cecil Graham: What is a cynic?

Lord Darlington: A man who knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing.

We’ll cover the many simple and complex costs associated with this medium. But don’t lose sight of the value too. Open source software carries value beyond what’s coded and licensed. Participating in this valuation is where community forms.

You might have hesitated at the sheer size, the complexity of the tooling, or the pace of the community. It’s intimidating to engage with something mature and existent. They have a circle of friends already. I don’t belong here. But I suggest: you need not see these communities as in and out groups. Nor do you have to be a midnight developer. Participating within the open source software ecosystem can be a steadfast, rewarding exercise even when your work isn’t the next blockbuster community darling.

It isn’t a one-sided exchange either—playing the part of the audience is as essential to a successful performance as playwright, stagehand, or actress. We can engage with open source software along a broad spectrum of activities, activities that appeal to every skillset, experience level, and time constraint.

What is Open Source Software?

Before we get too far, I should summarize how we got here. Folks in the 70’s and 80’s were bartering electronics in garages and parking lots as part of movements like the Homebrew Computer Club. Hobbyists shared patches of software built atop these machines and operating systems, sometimes with dubious and uncharted legality.6 The collective sharing spirit was strong, yet competed with corporate interests. Free software threatened these proprietary software monopolies. The GNU foundation states: “The nonfree program controls the users, and the developer controls the program; this makes the program an instrument of unjust power.”7 The message was bold, with little room for compromise. Early pioneers crafted memorable statements like “the four freedoms of free software”8:

The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose (freedom 0).

The freedom to study how the program works and change it so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1). Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help others (freedom 2).

The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3). By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

Open source spun out of this free software movement in 1998, the result of a concerted marketing effort accompanying the free release of the Netscape Navigator web browser and its source code.9 The term open source, suggested by Christine Peterson, appealed to businesses balking at the idea of free software being unsellable and cheap. At its core, open source software is accessible code governed by a license—rules defining its use, reuse, and distribution. Since 1998, the Open Source Initiative maintains a formal definition of what constitutes open source, as well as which licenses adhere to this definition. The summary here is a window into a neutral, open-playing field10:

- Free Redistribution

- Source Code

- Derived Works

- Integrity of The Author’s Source Code

- No Discrimination Against Persons or Groups

- No Discrimination Against Fields of Endeavor

- Distribution of License

- License Must Not Be Specific to a Product

- License Must Not Restrict Other Software

- License Must Be Technology-Neutral

Wow, that seems like a lot, doesn’t it? To be honest, I hadn’t even considered all those nuances until researching this book. But I’ve lived through some of these clauses coming into contact with communities. We’ll dive into that in Chapter 4. The important thing is, folks have been thinking thoroughly about how to create maximum access to software for a good long while.

These early ideas set in motion a lot of the mindshare we work within today. Supposed truisms like “given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow,” “contributions welcome,” or “release early, release often” feel like part of the DNA of open source, even as reality is often more nuanced than described.

We take this foundation for granted now, and have transcended it with a greater emphasis on community and inclusion. Corporate interests direct and divert energy into the movement, and it seems as if we’re always at the edge of crisis. We must expect more from open source and from each other. It’s not just a license or just code anymore. Social coding via platforms like SourceForge, GitHub, and GitLab revolutionized access and nurtured community like nothing before them, but didn’t always do it equitably or with safeguards. There is still more work to do. Mature community forms when people, tooling, and process combine to solve a problem. Lasting community forms when we have a safe place to participate and learn from one another.

Symmathesy: The Learning System

That last point is a great one to emphasize. Together, we grow and learn from one another in ways not possible alone. Our skill acquisition accelerates, our perspectives diversify, and our networks expand when we share experiences. Writer and educator Nora Bateson coined the term symmathesy to give this concept a single word.11 It’s derived from the Latin sym (together) and mathesi (learn). Bateson defines the word as “an entity composed by contextual mutual learning through interaction.” You never have to use the word synergy again.

If that doesn’t sound like the highest form of the human experience, I don’t know what does. It’s not just the individual, nor their output, but the ripple effect we have on those around us. Imagine a graph of vertices and edges representing a system. A moving web never at rest. Jessica Kerr applies the concepts of symmathesy to software development, where she describes a development team as a symmathesy, “composed of the people on the team, the running software, and all their tools.”12 The team learns from one another, users, and the software itself. The software learns as changes are made to it. The tools learn as the team turns data into information. It’s brilliant stuff—she continues13:

This flow of mutual learning means the system is never the same. It is always changing, and its participants are always changing.

An aggregate is the sum of its parts.

A system is also a product of its relationships.

A symmathesy is also powered by every past interaction.

Open source software is a form of symmathesy. As consumers, we are direct participants in this system, drawing lines as needed. As maintainers of an open source project, we increase the size, robustness, and interconnectivity of the web. Connection is inherent in every action. The documentation, the code itself, the dependencies on other projects—the sharing is explicit. And the best projects amplify their reach via community. Participants may not even know each other, yet issue logs, code reviews, forum discussions, chat presence, and events help build a collective understanding of one another’s common goals and challenges.

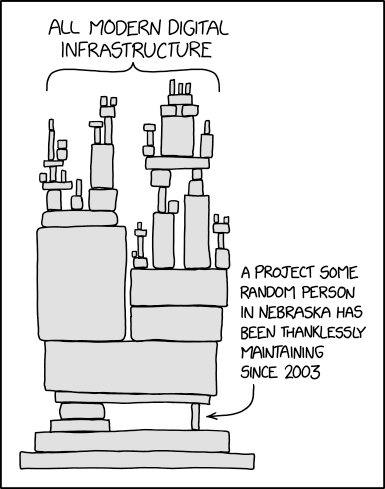

Individual projects can become a part of a larger ecosystem. No single person is responsible for these emergent systems, but these systems may become reliant on one. They’re interconnected, fragile, and prone to falling over. (FIG 1.1)14

FIG 1.1: an xkcd comic showing how all modern infrastructure, particularly open source, is an unstable composite, propped up by volunteers. “Dependency” xkcd comic courtesy Randall Munroe.

Cascading interactivity can lead to long, confusing open source dependency implosions. Projects and people can become victims of events many levels abstracted from their application code.15 Those aren’t fun days. But this same sprawling network creates resiliency in the system too. Projects that deviate from community expectations are abandoned or forked. People lose interest, give up, move on. A variant of the original project emerges, the system reshaping itself. Sometimes those unexpected events surprise us. Community as an ever-changing web composed of us and our actions, learning together.

Act Like an Improv Artist

If you’ve ever gone to an improv event or seen one on television you’ll understand the concept of yes, and…. This phrase challenges the artist to incorporate input from others and evolve their own approach in kind. Yes, and… “is a state of mind that all of the performers adhere to.”16 Embrace and extend. Acknowledge and advance. Yes, I will use that salmon you handed me to call my boss and demand a raise.

It’s called the first rule of improv because continuing the narrative while adapting to external circumstances is essential to connecting to the audience. How well the artist accomplishes this without hesitation helps the scene. It’d be a bummer if they threw their hands up and said, “no, I don’t want to break into song and dance right now, can we do something else?” Or, “no, the landlord didn’t suggest we sublet with four robots.” Improv masters think on their feet, build upon a shared story, and continue pace. Audience participation is the best catalyst, even if they need coaxing. Together everyone learns what the story is and where it’s going, creating a community through trust and practice.

Using and maintaining software is a constant improvisation. Generals for over one hundred fifty years have said, “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” I’ll borrow from another general in adding that, in some cases, we have met the enemy and they are us. Turns out, we’re wildly inconsistent as a species, let alone collaborative software endeavors. The slickest project plan in the world cannot account for the speed of open source.

What is the speed of open source? It’s both imperceptibly slow and breakneck fast. Every day a social media feed teases something new. Must you stop to learn it? Am I missing out? Something is broken and the status quo is at risk. Take dependencies. It could be that 0.X version of a library that hasn’t been updated in three years, suddenly releasing a compromised version due to missing two-factor authentication on the maintainer’s npm account. It could be a maintainer forgetting a file and publishing a broken release. Or it could be a well-known project unwittingly releasing a breaking change during a routine update. When these things happen, often there are high-profile herd-like behavior shifts to other packages, workarounds, reversions. Oh, and plenty of angst.17 Someone might propose a solution and the maintainers need to quickly assess the risk of merging that change. It might be against current patterns, lack tests, or add yet another configuration option.

As bystanders, we need to assess how to move forward with our own consumption plan. How we respond to those moments is key to the long-term health of the project. As a group we work to learn and apply new knowledge in this ever-changing environment.

Seek Reciprocity In Relationships

We don’t work in silos. Even as individual contributors, freelancers, or lonely teams of one, we interact with other people, or their facsimile products, throughout our workflow. You might be designing a site for your partner’s business. They will review, interact with, and be affected by the impact of the site on their end users. Making the site useful, accessible, performant, and maintainable helps all parties continue to engage with one another. A deficiency in any other of these areas imbalances relationships. Often the user is the victim of these imbalances, and they may leave as a result. You miss out on user flows, feedback, or revenue.

Ask yourself, “what is the expectation I am suggesting?” If you wish your project to go beyond “be glad it exists,” you must design your users’ experience. The lack of this design is a choice as well, but not a very responsible one. What does someone get for investing their time in learning more about your project? Are you respecting their time as much as yours? Are you setting them up for success or failure? The absence of this balanced equation between parties creates incongruent relationships.

Irresponsible sharing of maintenance can lead to atrophy, risk, and wasted effort. Our intentions are not enough. Think of this as the squandering of a public resource. Someone else will pick up that litter. That dude cut in line, so I can too. I don’t need to report the issue, or follow the issue template. Collective inaction, missing governance, or everyone expecting others to pitch in can lead to erosion of a once-firm footing. Find ways to over-communicate your intent or your understanding so that assumptions are lessened and agency is clearer.

Your intentions must be defined and implemented via specific policy. Park staff can place garbage cans all over the picnic area to encourage responsible disposal. But then they need to pay someone to empty them, and they attract bugs and pests. Or they can be bold and have no garbage cans; instead installing signs to “leave no trace” and to haul away refuse as you leave. Radically different approaches rooted in the same goals. The expectations are clear in both policies—the maintainer communicates; the consumer must respond. Lots of open source projects suggest that you open an issue clarifying work and claiming it as your own before beginning development. This gets everyone on the same page before committing a single line of code. Others may tell you not to “lick the cookie,”18 or claim a task with best intentions but never complete it. Use the contribution guidelines when considering contribution. Observe and emulate patterns of behavior when approaching a new community. Don’t litter, and don’t pick the wildflowers.

It’s too easy to fall into this familiar consumption pattern with open source software. We take but never give. We are busy. Too many issues to wade through for a solution. Another npm install doesn’t hurt, does it? Well, aggregate web page analysis19 shows broken budgets across size and request count metrics. As consumers of open source software, we must be aware of our part to play in perpetuating incongruent relationships. We must likewise consider the people creating open source software. A download isn’t enough. Waiting for someone else to report it or fix it isn’t enough. Donating may not even be enough. Maintainers crave our time20 (mentioned 12 times in a single comment by the Moment.js maintainers). We need to invest in the projects we use via thoughtful engagement.

Denis Pushkarev highlighted the incongruity he experiences as maintainer of the core-js polyfill library. He penned a lengthy (a quarter the entire draft of this book) accounting of the imbalanced relationship the world’s largest websites have with his project, built to shim old and new web features to the broadest set of browsers. By his measure, his code is used by over fifty percent of the top ten thousand websites and seventy-five or eighty of the top hundred.21 According to Pushkarev, that’s an install-base only surpassed by jQuery. He doesn’t point this out looking for kudos, “but to show how bad everything is.” At the time of writing, Pushkarev claimed full-time development amounts to about four dollars an hour. Atop all of this, he calls out the targeted abuse he routinely receives because of his efforts to earn more. His is a common perspective, and informed from experience, not social media punditry. Anyone would question their resolve with these factors arrayed against them.

We must do better. We must rebalance relationships as consumer and producer.

Observed Systems Are Changed Systems

Complicated things are better understood when taking them apart. The totality of the machine may be hard to grasp at first. But gradually, with both study and practice, the complete picture is rendered in your mind. Other times you surprise yourself with a discovered inefficiency—something that can be added or removed to improve the whole.

Outside scrutiny will most certainly impact the mood, trajectory, and lifespan of a project. Public code simultaneously informs and is informed. Symmathesy. Remember, an audience has as much sway and investment in a successful performance as the players. Knowing that you are being observed yields five to twenty percent scientifically measurable22 improvements in performance too. That’s why shipped is better than perfect, or why adopting the improv artists’ strategy of yes, and… encourages a growth mindset. You’ll be better prepared to contribute to a project if you are in close proximity to it. Sit in the front row. Clone the project. Take it apart. Break the tests. Create a mental model of its uses and constraints as a composition arrayed against other factors. Formulate an opinion about the software and then see if it holds up to the opinions of peers.

Oftentimes the mere act of using software will reveal opportunities to improve it. A foundational python style guide states, “code is read much more often than it is written.”23 And once written, a maintainer may skim, internalize, or ignore their own documentation. The humble typo is a psoterchild of this behavior. The fresh eyes of someone reading the code for the first time, from a different context, will find something a seasoned or original contributor may miss. This naivety is open source gold—spend it generously and hope your money is good where you choose to send it. Maintainers not listening are not worth your time. Maintainers of mature projects will create pathways to contribute documentation or code comment fixes with as little friction as possible. As a maintainer, encourage raw, inquisitive, and “stupid” questions. Under their surface is usually an unmet need or an assumption to be rooted out in the code or docs. For every person that comes to you with a question like this, imagine dozens more getting stuck and saying nothing. These folks using your project are choosing to engage with you—I promise that’s a big deal.

Abstractions

I’ve written this book as a new entry in the compendium of open source thought. I don’t fancy myself a thought-leader and for that we are all fortunate. But it is informed by years of success and failure working with open source software. The advice is honest; the vision bold; the mandate modest. I was once hesitant to understand where I fit in the open source community. I suspect some of you might feel the same. I found footing in a project called Pattern Lab,24 within which designers and developers could create larger and larger components using atomic design patterns. I enthusiastically used, contributed to, forked, maintained… and burned out on it. It was as frustrating as it was rewarding. It taught me what I hope to teach you. Open source brought about the best in me, not because of any particular commit or feature, but because of the vehicle it was to further my connection to others. I hope that sounds as exciting to you as it still does to me.

We constantly swim in the wake of others, creating our own as we go. We are both consumers and producers of what Brad Frost calls, “creative exhaust.”25 He says, “It’s not about the work you do, but rather what that work enables others to do.” We work together and apart toward goals, never quite seeing the fullness of the web. We sprawl and simplify. We diverge and agree. We construct and abstract. Daily life is an abstraction: from wheel to automobile, from lightning to lithium battery, from rice to risotto. We build upon the work of one another, combining ingredients, remixing content, drawing new connections. We are part of a symmathesy called humanity, or maybe jQuery, depending on the grandiosity of your focus. We push and push against boundaries until they give way, if only a tiny bit at a time. Open source is like this in its best incarnations. Keep pushing. Find your community. The remainder of this book will show you how.