Chapter Two

The Spectrum of Engagement

Many hands make light work…too many cooks in the kitchen…there’s plenty of dueling idioms to describe collective behavior. As our community increases in size, so too can our motivations clash and our individual skillsets complement. If you caught the tension between these phrases, good! Open source software development exposes us to this paradoxical environment. We each seek value by engaging within our capacity. And we do that in a surprising number of ways. I define them as consume, contribute, maintain, and empower. I want to show you that there is so much more to open source than “just”26 using it.

Value Exchanges

My then ten-year old son Max, when learning about this writing effort, said “I have one suggestion as you write your book, use a few analogies.” Last chapter had plenty of those pretty overtly positioned to align with open source software—though I posit a last one (okay probably not the last): gardening. It’s not a novel analogy, as others like Maggie Appleton use it effectively to organize content,27 but it furthers our narrative—if only we dig in a bit.

A garden is an intentional arrangement of plants. We shape the earth, enclosing and manipulating it for a purpose—cultivation, ornamentation, soil-retention, nature-preservation, research, or otherwise. It can vary in size, site, crop, focus, and care requirements. We derive different values from each garden, depending on the motives and needs of our context. Software comes in all configurations too—personal, proprietary, open source, small, large, weed-ridden. Let’s focus on that open source one. Maybe you see where this is going.

FIG 2.1: A community garden is the intersection of many needs and skillsets, each as important to the success of the effort. Photo by Steve Adams on Unsplash.

Envision a community garden (FIG 2.1)28: now there’s some fertile territory for analogy. Max will be proud. Many actors combine efforts, motivations, and needs within a singular plot.

This garden requires planning across every dimension. You need physical space. Is a location secured? Is it near people that can work and benefit from the yield? What will the layout of the space be? How will plots be divvied up? You need raw material. How do you pay for the soil, tools, seeds, water, and fertilizer? Do you need a fenced enclosure to keep out deer and rabbits? What will you grow and how will it not die because everyone else thought the other folks would water and weed once school started and it got busy?

A critical point to be made here is that you need not know all these answers to participate. Maybe the spark of engagement is accepting some free, surplus produce from this year’s crop. Maybe you start with gumption and a trowel. Or nothing at all but your attention and time. By gardening a bit yourself, or if you’ve grown at the community garden for a couple seasons, you’ll accrue general and specific expertise that makes you more and more comfortable taking on tasks. Through proximity and persistence, you might one day find yourself managing the fundraising campaign, mending the fences, bringing the produce to a local shelter, recruiting neighbors to pitch in, or assigning the seasonal plots to keep the Montagues and Capulets separated from one another.

The sowing of seeds, mulching, watering, weeding, harvesting—you know, the actual gardening—that might take a back seat to the needs of the moment or your shifting interests. And that’s okay! Because at this scale no one person can do it alone. Rather, it takes a group of committed individuals—a literal community—working together to make the effort succeed. The array of activities we choose forms a spectrum. We might not undertake tasks along the spectrum all at once, in sequence, or at all. Tasks may change in complexity, responsibility, or time-investment. We generate different values from each of these actions, each an investment in the whole.

All of this takes time. Gardens are not transactional—they are a relationship, a long-term investment without the promise of success at the outset. The time and care needed to nurture a seed through to harvest requires more than a moment or payment. Of course, you can buy a carrot for less money than your time is worth growing one from seed. But that’s not really the point. Instead, the payoff—the value—is both the process and the product. Working in a garden has an implicit value exchange: effort and resources over time create value. Open source software value maps to this same exchange. Time is our currency, whether that’s:

- conserved in using someone else’s code

- wasted as a result of poor implementation, bugs, breaking changes

- invested via contributing fixes and features

- donated to others through maintaining

A transaction is momentary. What open source projects create are natural opportunities for lasting association. And the best part is, we can learn to think of these actions along a continuum wherein we can play the role or roles we want.

The Spectrum of Engagement

By consuming open source software during your day, you’ve already engaged within the open source ecosystem. But there is a more complete picture, defining a spectrum with distinct activities for different roles. A broad array of options lay before you, like all those tasks in the community garden. They all need doing and have merit in advancing project goals.

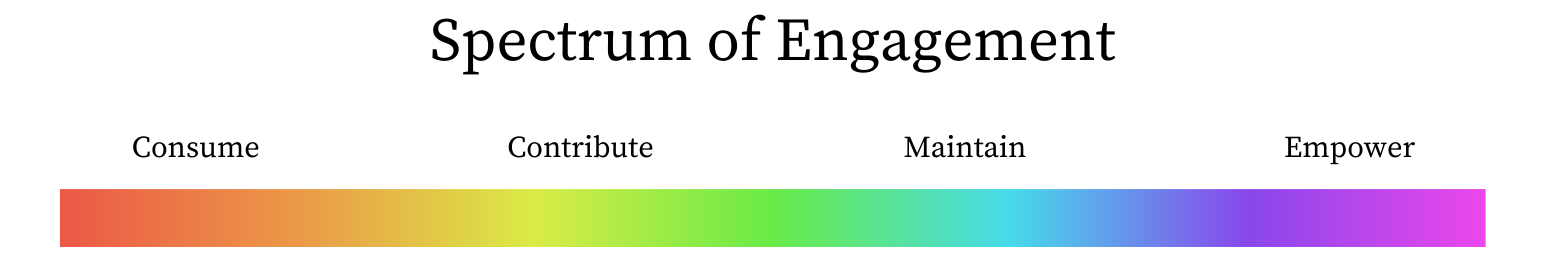

At one (or many moments), you may consume, contribute, maintain, and empower. This is the spectrum of engagement. (FIG 2.2)

FIG 2.2: The spectrum of engagement covers a range of activities that define how you can interact with a project.

This isn’t some abstract software concept. I acknowledge the cringe associated with business-speak like engagement and value exchanges and push past them. We can reclaim their humanity. Stay with me. One can overlay the spectrum of engagement atop most aspects of life and see the range of community-driven action. We are at all times exposed to, and, if able, participatory in community. Even if you don’t directly act, you are affected. More on that in Chapter 6. Let’s apply the spectrum of engagement outside the realm of open source or even tech. Think of another intersection of actors and activities: accessibility in businesses that are open to the public. The goal is equitable access to goods and services.

- Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act29 outlines the criteria and requirements businesses must comply with.

- Not only do persons with disabilities benefit from increased access, but everyone according to their situation and context.30

- The communities they participate in and businesses they patron benefit from their presence.

- Engineering firms and architects comply with federal standards when drawing new plans. They factor in braille signage and accessible switches, hooks, door handles, grab bars, dispensers, driers, and restroom fixtures. They design adequate flat maneuvering at the top and bottom of ramps for motorized scooters, wheel chairs, and service animals.

- Organizations contribute to these outcomes with direct advocacy. The Barrier Free Golf project in Chaska, Minnesota designed a first-of-its-kind golf course promising “people with disabilities, veterans, juniors, and beginners of all ages access to fun golf.”31 The Ramp Up Iceland project32 organizes construction of access ramps across the country.

- Litigation in pursuit of equity bands interests together toward common goals too, such as when the City of Philadelphia settled in court to upgrade ten thousand curb ramps around the city.33

Maintaining these efforts requires investment, regulation, and willpower. Empowering change in the first place sometimes requires a community of citizens or concerted lawmakers, but always benefits from an engaged populace.

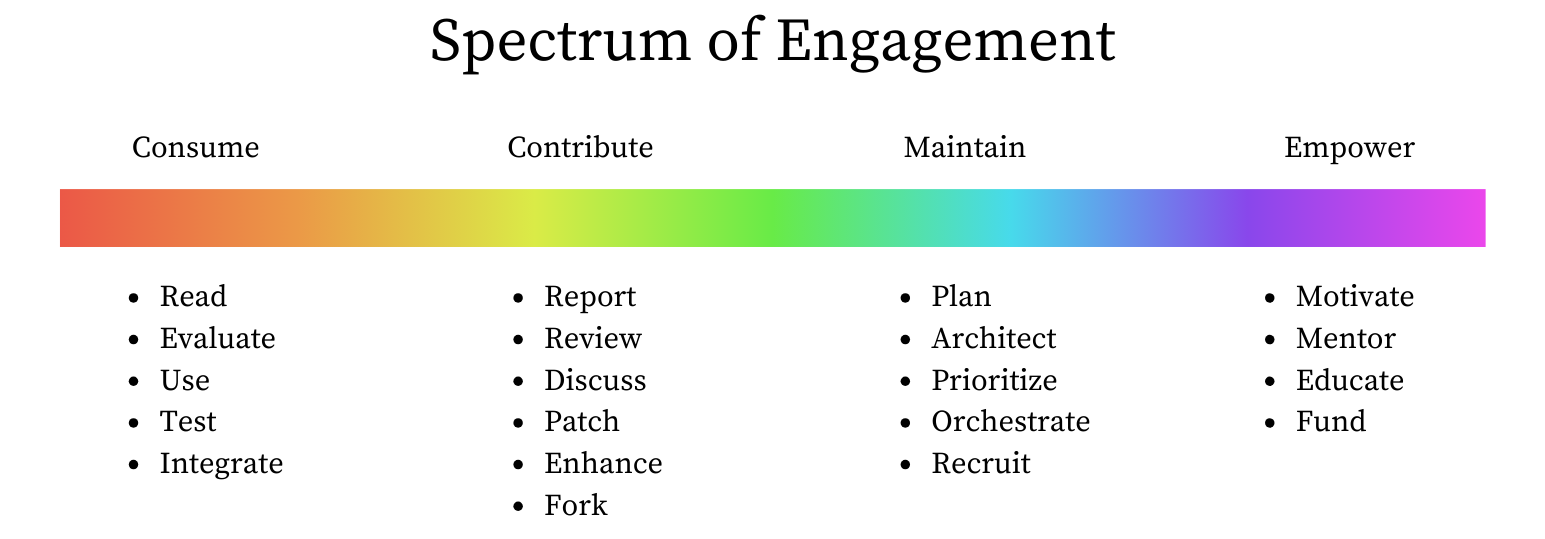

The spectrum of engagement applied to open source software allows you to dive in across a range of activities. (FIG 2.3) It’s user-centric and not necessarily oriented toward growth from a maintainer’s perspective. You don’t have to do the “lower” tasks before leveling up to the “higher” ones. I suggest they are all of value to a mature project. Growth in role happens, but it’s not the outright goal.

FIG 2.3: The spectrum of engagement contains many tasks that further the goals of a project.

Your familiarity with an open source project will increase from using it. One day, reading the docs for a tool brings you to their issue log after you notice a small typo. This is a moment of action, if only you pause to take it! You submit the fix for the typo, a small but engaging moment. You usher the patch through their pull request and deployment process, learning a technique or two along the way. You’ve converted a bit of your time into advancing both the project and your knowledge. You didn’t set out to “do open source,” as Salma Alam-Naylor suggests34:

Asking “How do I get started with web dev?” is like asking “How do I get started with cooking?” Decide what you want to make. And then reframe the question.

In your case, you decided to improve a specific thing and went from there.

All parties benefit from the spectrum of engagement. We all want value from our efforts, even if we don’t consciously think about it. How is our time and attention balanced out on the ledger? Everyone wants expectations set and met for their investment. As users, we can be vocal in support and constructive in critique. As maintainers, we can be clear in values, priority, and polish. We can make pathways to increase engagement. We all, as participating citizens in this ecosystem, can affect the most change together through discussion, collaboration, and listening. Our roles may change per project, per ticket, per day. Let’s examine these roles and their activities, engaging along the spectrum.

Consume

Sort of like hosting in “the cloud” means hosting via “other people’s computers,” consuming open source software means using “someone else’s code.” Kelsey Hightower expands on this trope, revealing the depth and specialization behind it all:

The cloud is just someone else’s computer, power, cooling system, underwater sea cables, networking equipment, data center and the land it sits on, insurance policies, roadmaps, and a whole lot of people to build, secure, monitor, and support all of the software that runs on top.

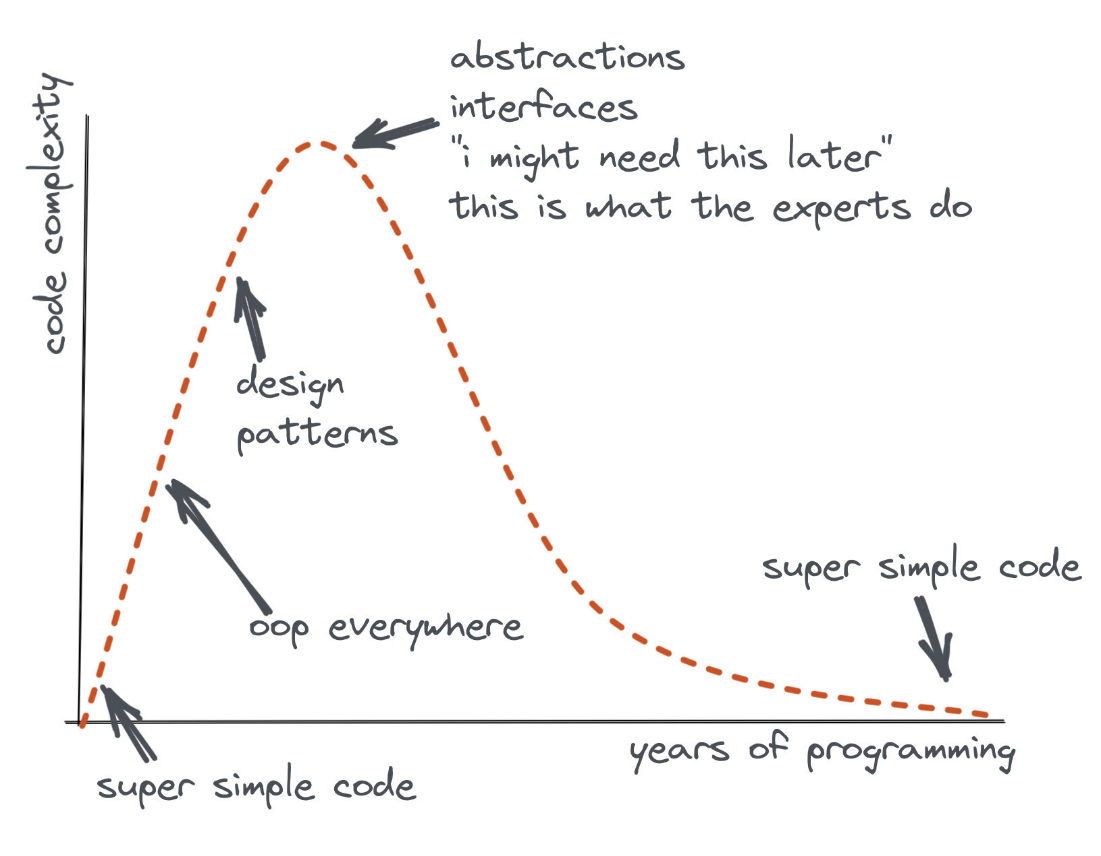

We’d be mistaken to think of the cloud or open source software so shallowly and without regard for the humans on both ends. This is where the value exchange between user and maintainer can feel most imbalanced along the spectrum. We may feel guilt or imposter syndrome consuming someone else’s code rather than writing our own. After all, if I don’t parse and localize those dates from the database myself, who am I as a developer and person!? Fear not! I challenge you to feel relieved, resourceful even. This may actually be a form of maturity—one often remixed within memes highlighting that both newbies and experts enjoy simplicity—yet a sizeable group of folks work harder in pursuit of intellectual purity. (FIG 2.4)35

FIG 2.4: A bell curve of programming effort expended as someone gains experience. Beginner and expert alike chose simple solutions while those with mid-level experience work harder at dubiously useful endeavors or optimization. Image by Flavio Copes.

Consuming open source software exposes and expands your skillset and approach. It is a form of risk; a calculation that, if conscious, can keep you moving. We’ll talk more about this tightrope walk next chapter. As you work in this space, you’ll notice organic opportunities not only to learn but also to share what you’ve learned. This is your superpower. You will formulate opinions, perceptions, and maybe even expertise in the tools that you use—don’t keep it to yourself! The work you’ve done leaves callouses and wisdom. In what ways can we consume open source software? I think you’ll be surprised at the array of activities before you. Let’s break it down.

Read

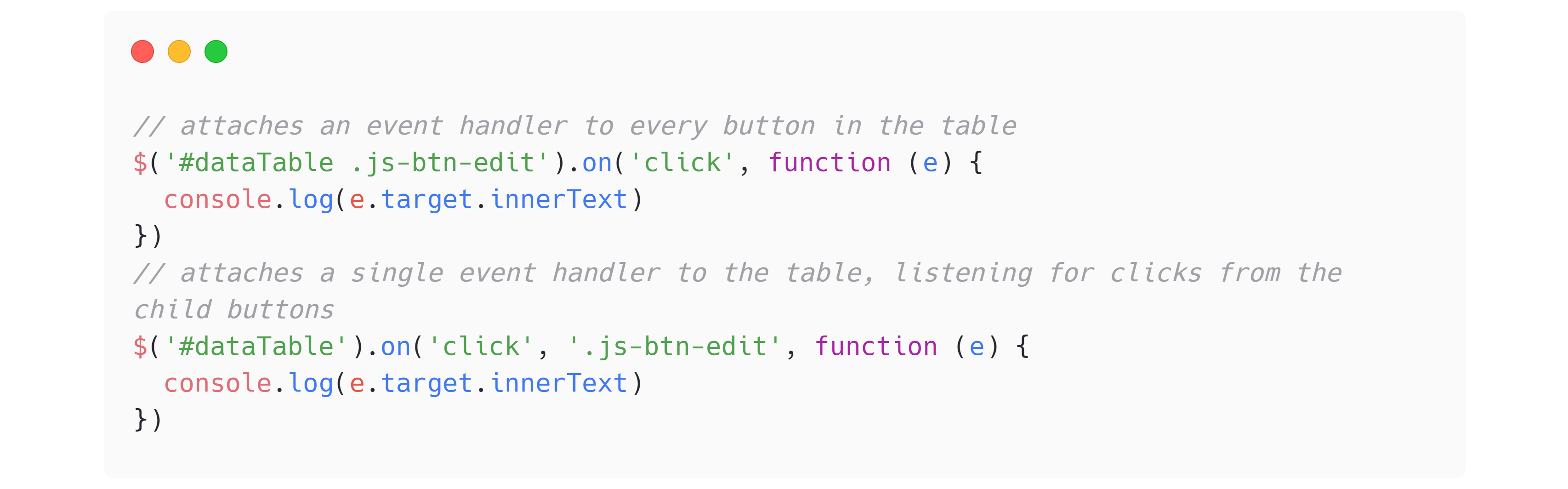

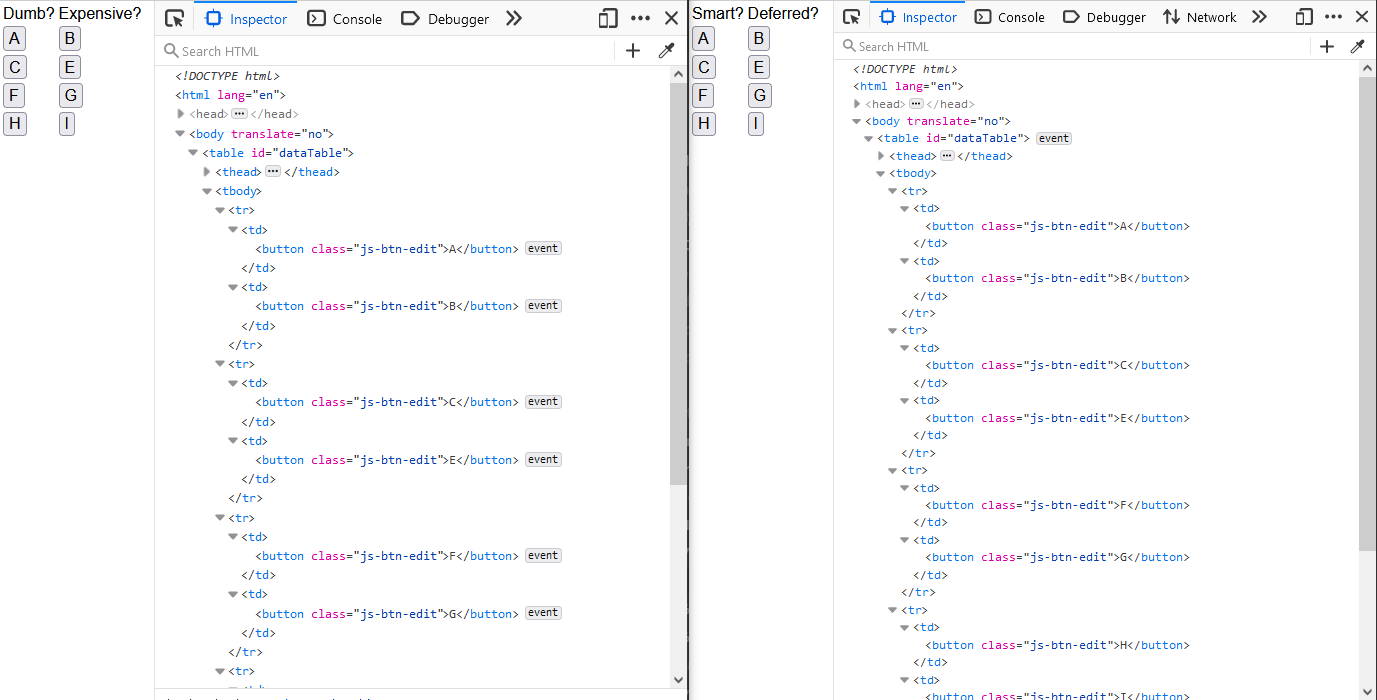

Learning about a particular piece of software increases your awareness, draws connections based on existing context, and helps you align it against the mental model of potential utility. I remember reading of jQuery’s release (over ten years ago) of a new API that allowed teams to level up from direct to delegated event handlers.36 Rather than attach event listeners to the element taking an action, like a button in each table row, we could delegate the action upward to the table itself. (FIG 2.5)

FIG 2.5: Optimized event handler registration made possible with a newer version of jQuery.

The functionality is the same and the syntax similar, but the performance impact compounds the more rows you add. (FIG 2.6) More importantly, the on delegation method also handles future items being added to the DOM, eliminating entire classes of concerns for web developers. For example, adding items to a list or table wouldn’t require you to add more event handlers. This small change improves flexibility, code organization, and readability. Reading about this only clicked when I could piece together jQuery in relation to a browser’s native event model.37

FIG 2.6: jQuery examples of direct and delegated event handling. On the left is the inefficient event handling strategy, with a handler on every button. On the right is the efficient, delegated event handling strategy, with only a single handler on the table.

I was more prepared to assess event binding scenarios in my work and others’. My novice eyes opened to the idea of maintainability and algorithmic efficiency within a website and how developer decisions could directly affect DOM performance and end-user experience. We must educate ourselves to better weigh tradeoffs like this, whether it’s jQuery API choices, CSS pre-processor bloat, or React layout thrashing.

Evaluate

Comparing one piece of software to another, or against criteria, helps you discern what matters most. Objective analysis is not always possible, but grounding your evaluation against known constraints can help sift through signal and noise. Busting out a weighted decision matrix in Excel is a great way to make friends at parties, and it also helps you slow down and apply reasoned rubric of thought to a situation. I’ve already had to defend evaluation decisions about software made many years back. Having a thorough evaluation procedure, data, and stakeholder buy-in helps maintain alignment. It also gives you headroom should things not work out. We’ll cover all this in more detail as it applies to dependencies in the next chapter. Isolate to understand how a solution works before comparing or integrating it. With content delivery networks (CDNs) hosting libraries and online editors, it’s never been easier to play with a project for little-to-no investment. Comparing and contrasting solutions prepares you to speak up or have opinions about one piece of software over another.

Use

Exercising the API is a surefire way to better understand the software, if only at a surface level. I’ve used that acronym a couple times now and it would help to define it. API stands for “application programming interface.” You can think of this as the public-facing featureset, be it a web service, a library, or maybe even a product. In a more technical sense, an API is the contract the software makes with its users. The API for a calculator has an addition function that says, “you give me two or more numbers, I add them together and return the resulting sum.” You will inevitably find a missing feature, deficiency, edge case, bug, or oversight when using software. This can lead you down many paths of engagement. Do you look at the documentation? The source code? The issue log?

Test

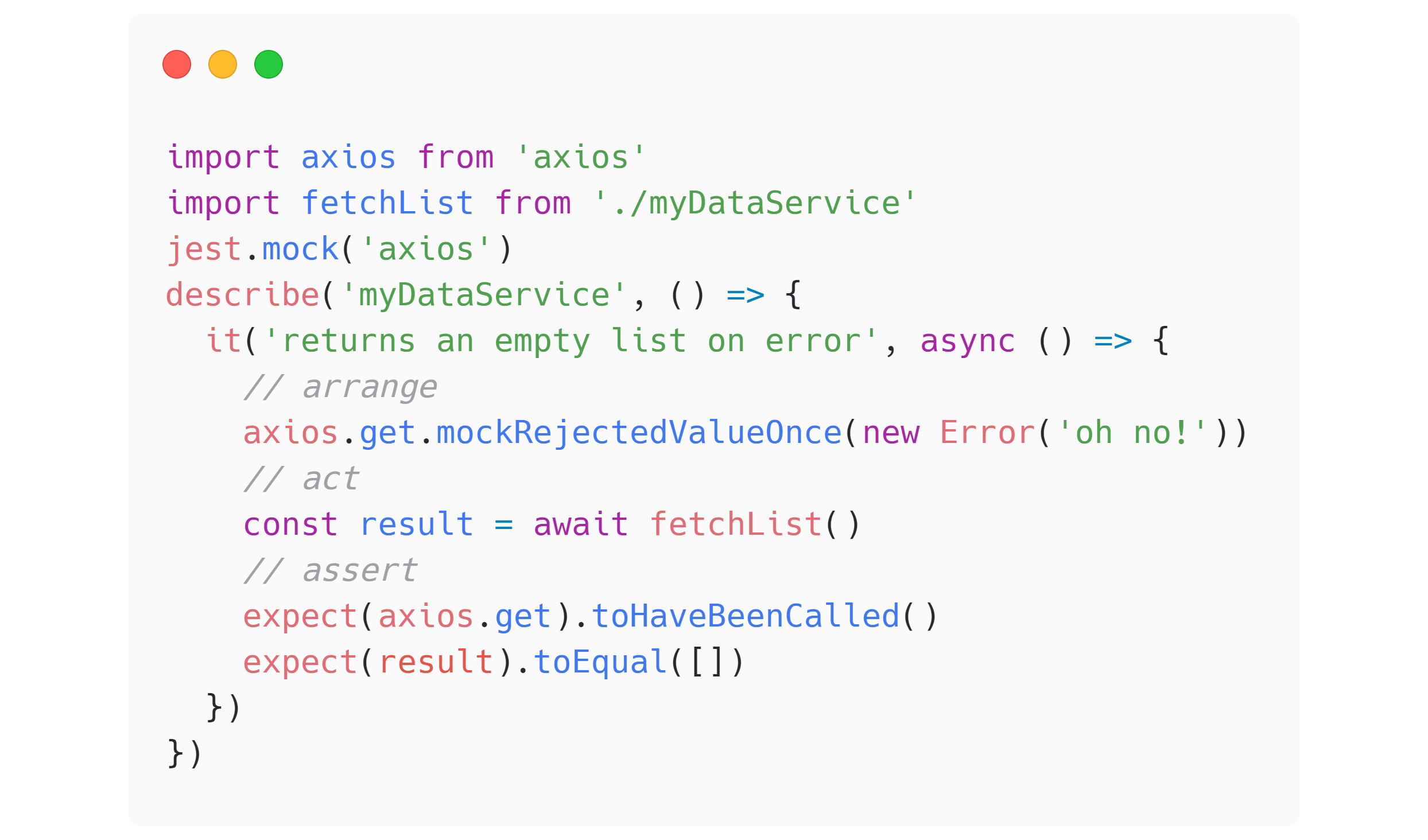

As the amount of software you weave together increases, so too may your desire to have confidence in those bonds. And we don’t want to test someone else’s open source code—they have their own tests, right?—so what can we do? Testing your own software alongside open source code often leads to the need to mock out APIs. Mocking, especially within unit tests, limits the scope of your test to the code that you wrote. Many testing tools provide a means to mock third-party dependencies. Here’s the Jest library testing a function called fetchList and mocking the axios network library. (FIG 2.7) We mock the axios module to always error, and return a rejected Promise. The unseen fetchList implementation catches this error and returns an empty array. We learn a lot about axios’s API by testing it, such as its get function that returns a Promise.

FIG 2.7: A mocked instance of the axios dependency, which we learn a lot from by testing its API.

Mocking may eliminate the need to make a real network call, or replace specific time-based values with a static date and time. Doing this is a great way to get a feel for the input / output of an open source project, as you need to emulate the API of their libraries in order for your tests to use facades of the real thing.

Peeking at a project’s tests can often be instructive too. Mature projects will have exhaustive test coverage exercising their own API across different permutations of architecture, runtime, configuration, and language. I’ve seen hidden features, command-line options, and parameters only documented within tests. Tests may contain usage hints or constraints that can help you expand your opinion of a project. You may encounter a scenario or edge case a maintainer has not accounted for within their test suite; what a great opportunity to engage!

Integrate

Similar to testing, composing open source software into larger and larger applications, or applying them to solve new use cases, can increase your knowledge of the domain and toolset. This prepares you to engage and apply your learnings to other scenarios. Understanding where the software fits into a bigger machine forces you to work within its API boundaries, read its documentation, and think through how systems interact with one another. This consumption can be creative, divergent, and chaotic. I remember people doing things with Pattern Lab I had never dreamed of needing, let alone trying. My mental model didn’t align with their needs and had to expand. When those folks engaged with the project, they pushed the envelope, introduced a new capability, assuaged a concern, or made the project more approachable. We all had an opportunity to make it better.

As you use open source software, you might attune yourself to a vision beyond what’s available. It’s time to contribute.

Contribute

If and when the time is right, you might choose to do more. Active participation on a project can feel exhilarating. I remember the excited moments making my first pull request to picturefill,38 Scott Jehl’s JavaScript polyfill library imitating the proposed spec of the new <picture> HTML element.39 Discovering new tech being built in the open, and being in a position to help build it? It opened my mind to concerns broader than my current work, role, and skillset, all in a quite humble set of code changes. Connecting with other people around the world interested in the same things as me created comfort and energy. We as a community were in open dialog with each other as developers, specification authors, and browsers vendors. The results mattered, but equally so did the side-effects: symmathesy was occurring around responsive web design, image performance, and user experience.

The longest-lived open source projects tend to evolve tiered contribution models. This hierarchy is a product of size and conservatism. They may appear to be gatekeeping, such as the structure the Apache Software Foundation assigns to its projects’ roles.40 User → Developer → Committer → Project Management Committee Member → Project Management Committee Chair. Each role feeds into the next and has unique responsibilities. But beyond the structure, one realizes this is the spectrum of engagement at work again—participation begets increasing familiarity and responsibility within a project. The Node.js project uses a nomination process that highlights a potential collaborator’s total contributions, reviews, comments, and created issues,41 not just code pushed. This holistic model of contribution better recognizes the value exchanges inherent in the spectrum of engagement.

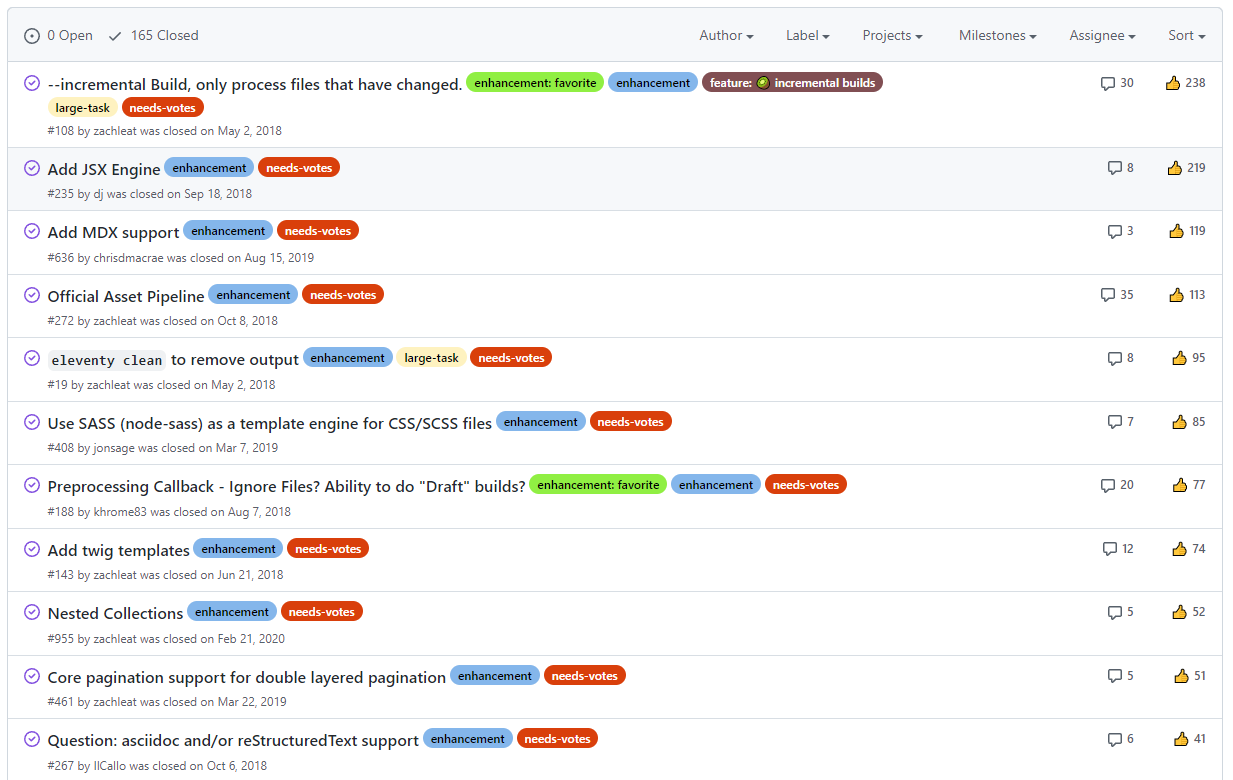

Report

Participating in an issue log is fertile ground for learning. They also need weeding, like any good garden. In the Node.js project, one of the better places new contributors can spend time is in triaging issues, “enabling newcomers another meaningful way to get engaged and contribute.”42 Some projects like lodash and Eleventy use a system where all feature requests are closed in the issue log but then voted upon by users. From a quick sort it’s easy to see what the community wishes, and how many requests need to be prioritized against each other. (FIG 2.8)43

FIG 2.8: Eleventy’s issue log wherein issues can be voted on by the community for prioritization.

Connecting with others encountering the same issue furthers your comfort with the project. Reading others’ issues builds empathy, and challenges or deepens your understanding. Corroborating an existing issue with more evidence helps maintainers prioritize work.

Speaking of maintainers, writing your own issues forces you to think like a maintainer. What is someone supposed to do with the information in your user report? Is it actionable? What can you provide to better compel them or others to action? A well-structured issue report is integral for time-starved maintainers to make sense of your problem, offer help, or suggest next steps. Take the time to review the project’s contribution guidelines and adhere to their issue template if present. Someone spent time to research how best to help you so the least you can do is listen to it.

Issue logs are a melting pot of cultures, skillsets, expectations, and languages. Assume positive intent here, but proceed at your own pace and comfort. They can be the public bathroom wall of open source, a place to scrawl grievances with little concern for repercussion or impact to the recipient. Try to frame your interactions as if you were talking in-person to a colleague. Engage only when you have the motivation and energy to do so.

Review

I saw Dan Cederholm deliver his Handcrafted Patterns talk at An Event Apart Atlanta 2012.44 What stuck with me from his talk was the ways in which we can learn from one another. Luke Wroblewski was also there and took better notes than me45:

There’s a common progression to learning anything creative: imitation, repetition, and finally innovation. Imitation: by doing what others have done. Repetition: learning and repeating patterns. At a certain point, muscle memory kicks in and you can use patterns without thinking. Innovation: apply your own creativity to the things you’ve learned. This adds your own style to things.

Seeing someone else do nearly anything, well or otherwise, can directly inform our own methods. Code-reviewing someone else’s work, or just reading it, can reveal novel approaches, new tools, and different thoughts. And, you might be able to do the same for them! If you are looking to help out within a mature or emerging project, but don’t know where to start, helping oomph in-progress work over the finish line is an admirable endeavor.

Discuss

Forums provide longer-form topics or dimensions parallel to the code itself. Some projects use discussions to announce new releases, or intentions to build new features as an RFC (request for comment). Message boards of any kind are a public means to rapidly build context necessary to make more effective contributions. Engaging in the discussions makes you better informed on the project, helps set direction, and builds your relationships with others using the solution.

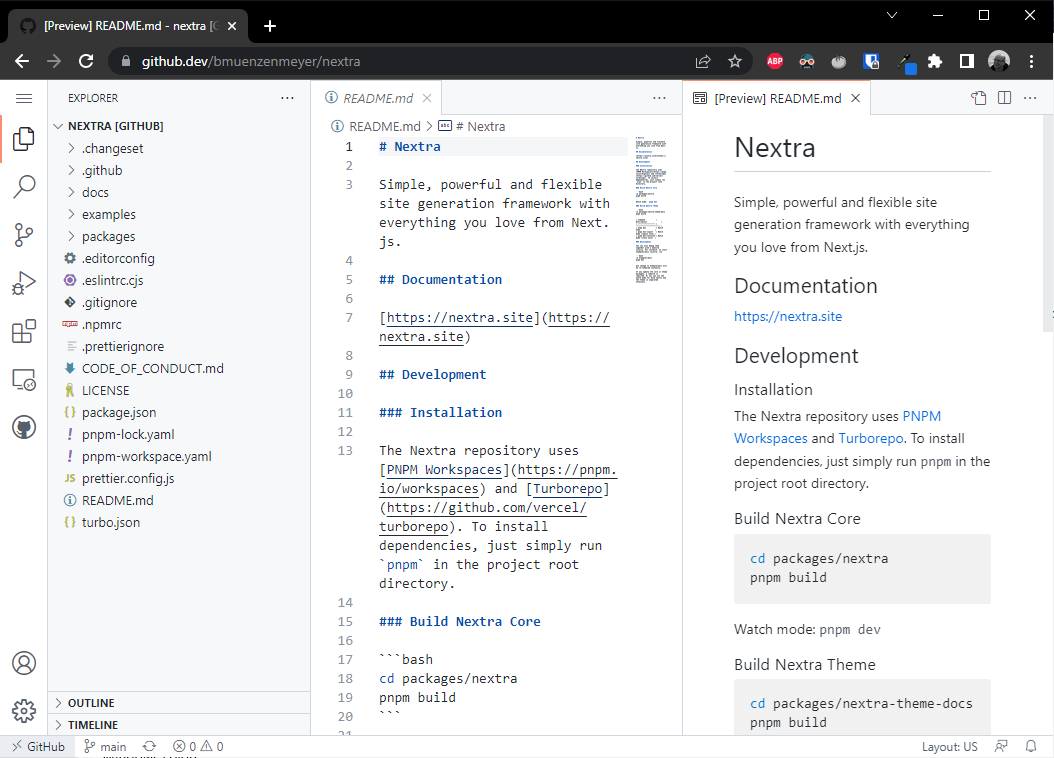

Patch

A patch is the gateway into larger forms of contribution. As mentioned, a typo or docs clarification is a great way to start this engagement. Tools don’t even require you to leave the browser, offering text editor capabilities per file or full-featured development environments. (FIG 2.9)46

FIG 2.9: A repository loaded within GitHub’s online editor. A GitHub codespace can further enhance this with a dedicated virtual machine, all within the browser. These features lower the barrier for entry for contribution.

The longer you use a project the more likely it is you will find something wrong with it. This is an opportunity knocking, don’t ignore it! Oftentimes a bug fix will expose you to the test suite, or the pull request process for the first time.

Enhance

Open source solutions often lack robustness in every use case or constraint. The projects “move at the speed of open source” or adhere to the notion of “squeaky wheel gets the grease.” And why wouldn’t they, really? We should only take what we need at the outset of a journey. Enhancements you identify or identify with can be directly contributed to the project—a ramping up of engagement that usually is a larger investment in time and code. Look again to an issue log for “good first issues” or items within your interest and skillset. Make meaningful contributions that advance the project forward, even incrementally. Familiarize yourself with contribution guidelines and the release process. Recurring work here, whether it’s feature work, fixes, updates, etc. is maintaining, which is a whole dimension that we’ll cover in earnest.

Fork

Within GitHub, forking is a direct copy-paste of the code within a project into another owner’s space. Many projects encourage contributors to work within their own version of the code, and then contribute back changes as needed. You might also find projects where you are tempted or outright encouraged to fork them. Forking allows for an inheritance of sorts of project code, goals, problems, and even community. Users within restrictive enterprise environments might resort to this as their only means of iteration. Decisions need to be made about whether or not to maintain a relationship with the upstream project once you have forked it. All in all, forking could serve a momentary purpose and then be deleted. Or it could become a sustained presence in the ecosystem, like it did when I forked Dave Olsen’s PHP version of Pattern Lab into the more comfortable and ergonomic-to-me Node.js version.

These are all great options if you’ll looking to give a bit back to the projects you rely on. Who knows, maybe you’ll become a regular.

Maintain

Someone that’s consistently acting in the long-term best interests of a project is a maintainer. It’s right in the name—they are invested in the project strongly enough to make sure it’s cared for. Maintainers can arrive at this point through two primary means:

- Original maintainers building the project from scratch

- Sustained contributors leveling up into long-term stewardship

However maintainers arrive, they must take great care to find balance. It’s naïve to think that any one person is an expert in all the dimensions that make a project successful, can do all of it at once, for a sustained period of time, and to a high-degree of satisfaction or effect. That’s why attracting a big tent of varied talent helps us assemble our open source Voltrons. Later chapters in this book dive deeper into maintenance concepts, so here we’ll only outline work significantly different than contributing. I sometimes see this rubber-stamped governance, but with little context. Let’s break it down into internal and external activities.

Plan, Architect, and Prioritize

Within any project, competing needs are inbound and released software should be outbound. Maintainers are air traffic controllers trying to land user, community, tech, and personal priorities. Without this work, we don’t have a project—we have a pile of code. Just some of the tasks in need of equilibrium include:

- Planning: You know, the “Who, what, where, when, why, and how” of any work. Keep a backlog well-maintained so you and contributors know what to work on next. The more detail, the better context for others to build from. But be careful not to overdo it—a logjam of good but incomplete and unprioritized ideas is almost worse than nothing. A good rule is if you don’t see getting something done in the next six months, delete it. If it’s important, it will come up again. Beyond six months, everything will have changed anyway—user needs, the technical approach, etc.

- Architecting: Adopt strong opinions about the foundations of the project. Define a set of principles and tech that realizes them. Be scrupulous about the encroachment of duplicate techniques dueling within corners of the codebase. This happens a lot with time and piecemeal contribution. It’s the maintainers’ job to maintain cohesion. Ideally, write down your technical stances so you can defend them, others can internalize them, and all can evolve when presented with new info.

- Prioritizing: Balance personal dimensions. Set boundaries of the work into your personal time. Calculate the trade-offs between decisions to tune the value exchanges your project offers. Know when to say “no” to a request or encourage engagement in the face of complaint. Think through proper succession planning should you hand over the project to others in the community.

Orchestrate and Recruit

There’s more to a software product than writing it. Tasks mundane, mandatory, or advisory all compete with individual contribution. A shift can occur with long-term maintenance, in that you code less, review more, and gradually find yourself more conductor than musician. Wow, the opportunity for another labored analogy is right there, but this time I’ll give it a rest.

In our efforts to sustain momentum on a project, we again need to balance:

- User needs and safety: Ensure the user of the software is not met with harm. Make the product stable, accessible, useful, performant, and adherent to data privacy laws. Keep an eye out for developer convenience running opposite user needs.

- Day to day: Shepherding contributions over the finish lines takes time-intensive review, written feedback, and testing. Many a pull request can get bogged down by something as simple as a merge conflict or broken test, but often a contributor won’t have the context of a maintainer to understand how to resolve it. Giving every little thing attention really adds up.

- Community expectations: Ensure the community remains healthy and engaged. Set expectations and plan to moderate deviations. For example, you might need to actively model constructive criticism and on-topic discussion. Creating an inclusive space for people to work is a prerequisite to the work. Increasing avenues to contribute to your project along the spectrum of engagement helps its long-term resilience and relevancy.

- Growth and support: Engage with your users to understand their goals and constraints. Approach potential contributors to gauge their motivation or self-efficacy. An enthusiastic newbie may be far more open to learn than a jaded or busy veteran. It takes time to nurture any new contributor, and it’s an investment with the risk of loss. Contributors aren’t a flock of sheep to collect and tend to—rather they are audience and actors at the improv show looking for cues.

These tasks are project-oriented investments. There’s another role, however, if your interests are more generalized.

Empower

Advocacy and enablement stand apart from consuming and producing open source software. Empowering others to engage in the spectrum of engagement makes for stronger, more inclusive communities. Within these communities we need space; and we can create space. The space we need is tangible and comes from others, like granting employees permission to work on open source projects (more on that later). The space we create might be a workshop we organize to open source an internal tool. Whatever the action, empowering others is multiplicative magic. It snowballs into far further outcomes than any individual contributor or otherwise “rockstar” developer can accomplish alone. So how can you empower others within the spectrum of engagement?

Motivate

Incentivizing engagement can sometimes be as simple as sending word to those around you. Ask. Tell them that you need help and want them to get involved. I only got involved with my company’s open source program office because someone had the wherewithal to identify my nascent interest and the initiative to ask. Thank you, Kristin, by the way!

Organizations, conferences, and businesses sometimes sponsor open source community events. All Things Open47 and the Linux Foundation’s Open Source Summit48 host presentations and day-long events intended to foster community growth and energy. They funnel attendees into advocacy and outreach topics specific to open source development.

The Hacktoberfest49 event every October encourages new and seasoned coders alike to find ways to give back to open source projects. Motivations here are usually pure—but so is my desire to eat less ice cream. The fact is, many projects are not staffed or oriented to handle the influx of new contributors. Overeager newcomers may overwhelm in their attempts to help, submitting poor quality changes like grammar semantics or arbitrary text edits. AI-generated contributions are suddenly more noise. Still, the event sponsors are going out of their way to improve our communities and open diversified “low or no-code” contribution paths that look a lot like the spectrum of engagement. I love these emphasized values upfront on their guidelines50:

Everyone is welcome.

Quantity is fun, quality is key.

Short-term action, long-term impact.

We can motivate in smaller ways too. Celebrate open source projects you use, trumpeting their success on social media or via thank you’s across their communities. Gestures of goodwill don’t always need to be grand for them to be impactful. A personal note may be worth more to some than any monetary reward.

Mentor

Continuing the personal theme, if you have the opportunity to mentor, do so. You will not be prepared—which is a good thing. I guarantee you will learn something along the way. Teaching others always forces an additional level of mastery in a skill—even if you feel like a teacher reading one chapter ahead of the class at times. The SSH key roadblocks that seemed insurmountable the first time you encountered them now represent a thirty-second diversion and a teachable moment. Helping others open source their work or contribute to another project boosts their introduction to the spectrum of engagement.

I had the privilege of mentoring attendees to Grace Hopper Celebration’s Open Source Day51 in September of 2022. Organizers primed dozens of projects and solicited for mentors to be on-hand virtually to support conference-goers in project setup, Git configuration, coding, and pull request submission. There were layers of responsibility between organizers, project leads, and mentors that resulted in a healthy stream of activity. By the end of the day I helped over a dozen attendees set up Node.js locally and work to make their first open source contribution to that project. It was rewarding to see them progress, and I learned more about how Node.js and the team operates. I found areas of concern while helping out and contributed back fixes of my own. The whole day was a formative example that engaging in even the largest projects is approachable to anyone, and it can be made easier via designed engagement. In 2023, I found avenues to prepare nodejs.org redesign52 work for attendees even though I had a conflict the day of the event. Participation along the spectrum of engagement felt palpable and fluid, depending on the moment.

The Outreachy organization53 aims to connect under-represented individuals with open source projects via paid internships. Web-adjacent projects Outreachy has hosted include Apache, Firefox, Git, Wikimedia, Yarn, and more. Mentors devote five hours a week to help interns with development tasks. Other volunteers are positioned to help answer questions and provide support. The structure of the program is well-defined and has many safeguards in place. The All In project54 similarly brings together industry partners and organizations with historically black colleges and universities to “create more inclusive open source communities for current and future developers from underrepresented backgrounds and regions.” It does this through intentional trainings, accessibility audits, language audits, and more. The value exchanges here are researched and equitable. Increasing diversity in open source only improves open source.

Large open source software foundations advance the field and create managed opportunities to engage. They actively court and mentor new projects under their wing, creating structure from an otherwise unruly ecosystem. The Linux Foundation, the Apache Software Foundation, the Free Software Foundation, the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, and the Mozilla Foundation, to name a few, provide broad support to their member projects, contributors, and users. They also act as a neutral party, shielding communities from the impact of corporate mergers, IPOs, layoffs, strategic pivots, and billionaire-fueled ego trips. This structure acts as an essential backstop on the open source playing field. We want more United Nations and less Batman.

Educate

Just like mentoring, creating learning content is an empowering act. Katie Sylor-Miller maintains Oh Shit! Git!,55 a community site so impactful to our shared understanding of version control fiascos that it has been translated into twenty-eight languages. Flexbox Froggy56 and Grid Garden57 challenge visitors to learn CSS concepts via open source browser games. These acts of creation directly educate visitors. Stephanie Eckles resurrected Dave Shea’s CSS Zen Garden58 via her StyleStage project,59 inspiring a new generation of experimentation, collaboration, and modern CSS tinkering in the open. All of these efforts are great applications of the open source model to not only teach via their content but also through their process. They demonstrate how to engage at an impactful level of the spectrum to benefit us all.

Fund

Free and open source software (FOSS) is sometimes anything but. There’s plenty of money to be spent and solicited for. Funding for the rank-and-file maintainer means anything from buying them a coffee to signing up for one of the many sponsorship routes available to projects and individuals. This value exchange replaces time for your pocketbook, yet the reciprocity can vary from project to project.

Do your research before sponsoring a project. Can you see an accurate accounting of project income and expenses? Some platforms like Open Collective60 answer questions like, “how do they distribute funds to their contributors? At what interval? What other expenses are there?” I audited a few larger projects and saw them sitting on a hoard of recurring monthly donations. That doesn’t feel like a successful disbursement plan. If you donate, do you get anything in return for your sponsorship, such as priority support, advertising, or kudos? Patreon61 provides built-in mechanisms for private content and tiers of rewards to funders. GitHub has sponsors-only features too.62

During a time of socio-economic upheaval caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, maintainers of the Jest project created public and private bug bounties. This enabled new and existing contributors to tap into Open Collective funds and in a small way supplement their disrupted income streams.63

Funding is not always a crowd-sourced endeavor, however. Organizations and companies can invest in projects, providing sustaining contributions and monetary aide for a larger impact. The OpenJS Foundation has twice partnered with the Open Source Security Foundation to sponsor significant investment in foundational ecosystem projects like Node.js and jQuery.64 Why these? Well, when your library is installed on over sixty percent of the top million websites, you become a project worth protecting.65 Government entities like the European Commission have supported hackathons and bug bounty programs to buttress open source projects across the globe.66

Come As You Are

We can only drive in one lane at once. I don’t expect or encourage you to do all of these things at the same, or with every project. It wouldn’t be healthy or sustainable. That road leads to fatigue and burn out. There is no explicit drive to climb the spectrum as if it were a mountain or linear journey. If that happens as a by-product, great, but it’s not the goal. I’ve outlined these avenues of engagement not to intimidate, but to inspire and re-frame open source contribution as more than hacking with a hoodie on in the dark of night.

All along the spectrum of engagement opportunity to work within open source lies. No type work is of more value than another. Mandy Brown writes in “No one is ‘non-technical’”67:

The categories of “technical” and “non-technical” serve wholly to privilege those in the former, at the expense of the latter. […] The “non-technical” nomenclature not only does a disservice to that work—and to those people—it also diminishes the ability of the organization to really get the most benefit from those skills. It’s difficult to earn value from the things you disparage, even if the disparagement is superficially polite.

Brown says that product teams, and by my extension, open source projects, would fail without the spectrum of engagement. The skills, temperament, and behaviors essential for a large software product to succeed must be derived from more than just the code. Acknowledging this need for balance, the All Contributors project68 helps recognize the multivariant output an individual contributes to communities. It offers a GitHub bot and CLI enabling maintainers to celebrate community work along the spectrum of engagement—at the time of writing thirty-three distinct activities.69 You don’t need a t-shirt, conference swag, or a bumper-sticker-laden MacBook to prove you are an open source practitioner.

Instead focus on the value you conjure, incremental and right-sized for the moment. That might be intrinsic, kept close to you alone, because it’s 4:14 PM and you have to save your work before getting to the bus stop, starting dinner, and cleaning the house for your in-laws’ visit tomorrow. Life is hectic and we should give ourselves grace in juggling it all. Folding the laundry can wait, as can open source. But maybe a spare moment lets you figuratively match and fold the socks: you send critical feedback to a project while you are using it, contribute that documentation fix or issue +1, or even ask a question yourself. You are furthering the discourse of the project with any amount of this work, however mundane, creating value from your time.