Chapter Three

Consuming Open Source Software

The thrill (or terror) of a blank file never quite goes away. You stare at the void, and the void stares back. You, at the start of a project, or a new ticket from the backlog, are met with boundless options to get the job done. Or instead of an infinite canvas, you see a brownfield duct-taped one-of-a-kind invention that is your ecommerce frontend. Looking at it the wrong way might topple it over. Hesitancy creeps into your thoughts, how should I do this? Have we done this before? Maybe you can borrow an existing pattern. Has anyone done this before?

The answer to that last question is almost always “yes.” It turns out, new problems are rare in this field. Rarer still are new solutions. Can we integrate something already written? You’re about to invite a powerful multiplier into your codebase—for better or worse. Its name is dependency.

Dependencies

The right dependency can propel or imperil your project. Using an open source library frees you and your team up to worry about other goals. You build real value if you meet user (and business) needs within the constraints imposed upon you. And let’s be honest—there is never enough time. If we can be faster and more efficient in one area, we accelerate the pursuit of other efforts. This can be a critical differentiator of success or failure. You may hit a deadline to ship a feature by offloading expertise and complexity. Or copy-pasting that previous trick. But sometimes a breaking change blows up your test suite and you need to decide whether or not it’s worth refactoring your tests or forgoing the upgrade again.

We make these determinations all the time, weighing options and outcomes. We engage in a value exchange with the grocery store to safely procure, store, and sell us lettuce as a direct abstraction of gardening. Likewise, we don’t often worry about how the chunked HTTP packets travel from server to client and back again. We trust that abstraction, click by click. We live within this omnipresent balance of trust and risk. We offload cognitive burden or material control so we have time to work on other things. Recall in Chapter 1 when we discussed an estimate that the demand-side value of open source software is nine trillion dollars. That’s how much money we’d spend to recreate our usage from scratch. We depend on tools and services to help us. But they can become so essential to our days that we become dependent on them.

Dependencies. A loaded term, it turns out. So that problem you were trying to solve on deadline? Someone has done the work. And they have open sourced it. And so have thirteen other people. Surely one of these solutions will work, right? But how do you know which one?

Packages, Packages, Packages

I will be framing the majority of our conversations about dependencies around the predominant package ecosystem of the day: npm.70 Its size (around three million packages) and entrenchment make it a tempting destination, and make it feel unassailable as a source of solutions. Who knows though, I doubt Bower maintainers envisioned its collapse.71 This guidance can be generalized to any managed dependency environment… be it Go’s modules, Rust’s crates, Python’s packages, Deno’s URLs, or you know, Oz bricks (when the next big thing arrives). Dependencies can come in other forms, too, not just downloaded text files we execute in a trusted environment. Oh, wait, exactly like that. Avoiding the npm ecosystem and downloading files from a CDN like unpkg, JSDelivr, or cdnjs is still a form of dependency management, one that is both software-related and network-related.

Let’s Talk Codependence and Compromise

We need to adopt a nuanced and ever-present vigilance around dependencies. If we are not careful, we create a conflict of interest when considering them. Declaring this bias at the door is essential to meeting project or user goals. We are collectively compromised by the notion that salvation is at the end of the npm install output scrawling by on our terminals, every solution a single import away. It’s no surprise then that this easy access translates to increased page weight. According to the HTTP Archive, the median mobile page weight has sextupled in the last ten years, to over two megabytes.72 Sure, a lot of that is also imagery, but JavaScript accounts for a median twenty-one mobile network requests for four hundred sixty-one kilobytes, thirty-five percent of which appears unused.73

Don’t get me wrong—there are some truly magical dependencies out there. Not just toys, but things that solve hard problems. Take Browserslist,74 a tool that integrates into CSS postprocessors, JavaScript transpilers, and code linters. You specify a target set of browsers and the integrated tools adjust their output accordingly. Their default maps to > 0.5%, last 2 versions, Firefox ESR, not dead to cover most evergreen browsers, desktop or mobile, for around ninety percent global coverage.75 Say you want to exclude that CSS custom properties polyfill in your app bundle? Take the guess-work out of which browsers map to this feature and specify supports css-variables. browserslist compares that query with a database of browser features per version and results in at least ninety-seven percent global support. Progressive enhancement techniques shouldn’t be ignored either, such as @supports CSS rules.76 With a bit more upfront thought, you can enhance a user’s experience if their browser supports it—without the overhead of a dependency. If their browser doesn’t, you’ve already designed an accessible baseline. The approach right for each situation is a matter of consultation and compromise. But as a representation of dependencies offloading complexity, sign me up.

Some equate this over-reliance on dependencies to a “JS-Industrial-Complex,” as Alex Russel says, complexity for complexity’s sake. This leads to lock-in, specialization, evangelism, and a self-referential feedback loop to instrument, educate, and make sense of more and more layers of logic. JavaScript is cast as both the hero and the villain here. One sells us the problem while the other sells us the cure. But dependencies are tools to be wielded, and us as developers play the role required of us in the moment. I challenge you all to think beyond the false dependency dichotomy. Dependencies are a fantastic means to defer expertise and risk management, accelerate progress, and propel projects forward.

Where Do You Want To Spend Your Time?

Consider the trade-offs you want to offload to someone else’s scrutiny by taking on a dependency. You might not have capacity to write test coverage for every edge case your solution encounters. Accounting for every circumstance is expensive and must be weighed against the probability and impact of occurrence. What is the consequence if your software is wrong? Can it be right… ninety-nine percent of the time? Perfection and precision is an admirable goal in most things, but it comes at a cost. The now-deprecated Moment timezone library runs over one million unit tests in the browser.77 They run them so you don’t have to. (FIG 3.1)

FIG 3.1: In-browser unit tests for the Moment timezone library. All 1,391,014 of them.

This makes sense when you think of the Sisyphean task that is their mission—to keep in synchronization their library with the world’s decreed changes in time zones,78 such as the mess that is Indiana,79 or when Chile changed their daylight savings time to not disrupt an election. Thankfully, a standards body funnels these changes to downstream tools as a dependency. Libraries, runtimes, and browsers adopted this standard within the Intl API,80 distributed via engines like Chromium or Node.js via the Unicode Common Locale Data Repository,81 the International Components for Unicode library,82 and the time zone database maintained by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).83 Open source and public domain all the way down, with communities dedicated to keeping us all on time for that next Zoom call, PTA meeting, or dentist appointment.

If you write in-house code, does it need unit test coverage to build and maintain confidence? If I had to pick one, confidence is more important than coverage. Entire books and methodologies swirl around the Internet regarding tests, so I won’t attempt an exhaustive run down. But I will ask, how much do you need to know the code is working as designed? Try to stay out of the implementation details and focus solely on output. If your code doesn’t have output, consider how to rewrite it. Emphasize functional test suites that mimic real-user behavior. Watch out for tests that stray into someone else’s code. You don’t need to assert that Moment.js is working right. Remember the million tests they run? They got you. And yes, sometimes a missing test or use case is the perfect avenue for engagement with an open source project, but only go there when you’ve explored options or the omission carries impact and degrades your confidence.

Tech Debt

The more code we write, the more code we need to maintain. Dependencies give us an enticing shortcut—and as cuts go, short ones aren’t always among the worst. They are an outstanding way to graft disparate work together into what we pass off as a whole entity.

What’s important is a clear vision of your dependency as a form of tech debt. You may have heard that term before and drawn negative connotations. I think that is mostly fair as a lasting impression, but the reality is more nuanced than that. Tech debt is an accelerant to progress. Taking a dependency offloads work from already busy and burdened teams, a path to get where you want faster. The value exchange is clear: code now in exchange for reliance and patronage. It’s a form of indebtedness. If you’ve ever purchased a car, a property, or anything really on an installment plan, you are familiar with debt. It is prohibitively expensive to save up the entire lump sum for a purchase—you may be saving your whole life if you needed cash to purchase a home. (Look up the etymology of mortgage sometime.) But a line of credit extended to your family brings your goal within reach. We cannot function without debt.

The size of the debt is important to consider, both financially and when taking on a dependency. Small dependencies and APIs are quicker to swap out with a replacement or in-house solution. Large entities like a JavaScript framework might be harder to replace. You may grow accustomed to the amenities and ignore compromises you are making. Vendor lock-in via hosting deals, poor separation of concerns, and freemium adoption are all too common. The salesperson was quick to remind us of the nineteen cup holders on the SUV we briefly had, but downplayed the electrical problems that caused a dead battery six times in a year.

Many dependencies bring not only themselves, but their own baggage—transitive dependencies—a hidden clause in the contract that can sneak up on you and ruin a deployment or a day. We reduce the risk of tech debt default by keeping a clean and honest ledger of where our compromises manifest. Pay down your debt with version upgrades, testing, and continual evaluation of the dependency landscape. I suggest investing in tools tools like size-limit84 or Lighthouse CI85 to help define and monitor performance budgets as your codebase matures. You may need to rely on a dependency indefinitely, and that’s okay. Just be mindful of the choices you are making in the moment when that install command is on your clipboard—what value exchange am I getting here? What compromises am I making?

Another Kind of Compromise: Supply Chain Instability

Open source code dependencies couple your project to the outcomes of others’ work. This work isn’t your coworker Kyle’s bad push that had a merge conflict in it. This work is unseen, four levels deep in our dependency tree, published at all times of the day, and hard to plan for. We expose our solution to upstream events, and if we are not careful, can be negatively affected. Gosh, what a downer this whole chapter has become. By naming our fears, we can begin to understand and overcome them.

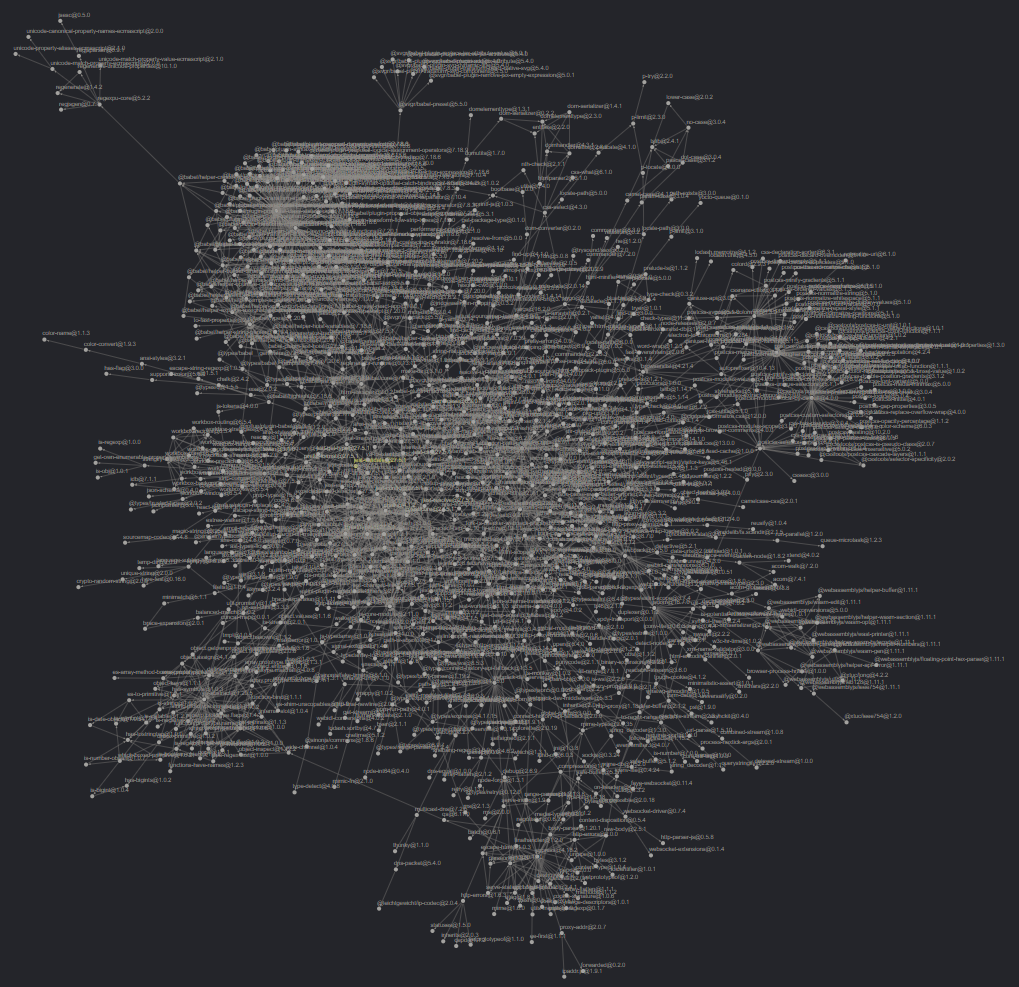

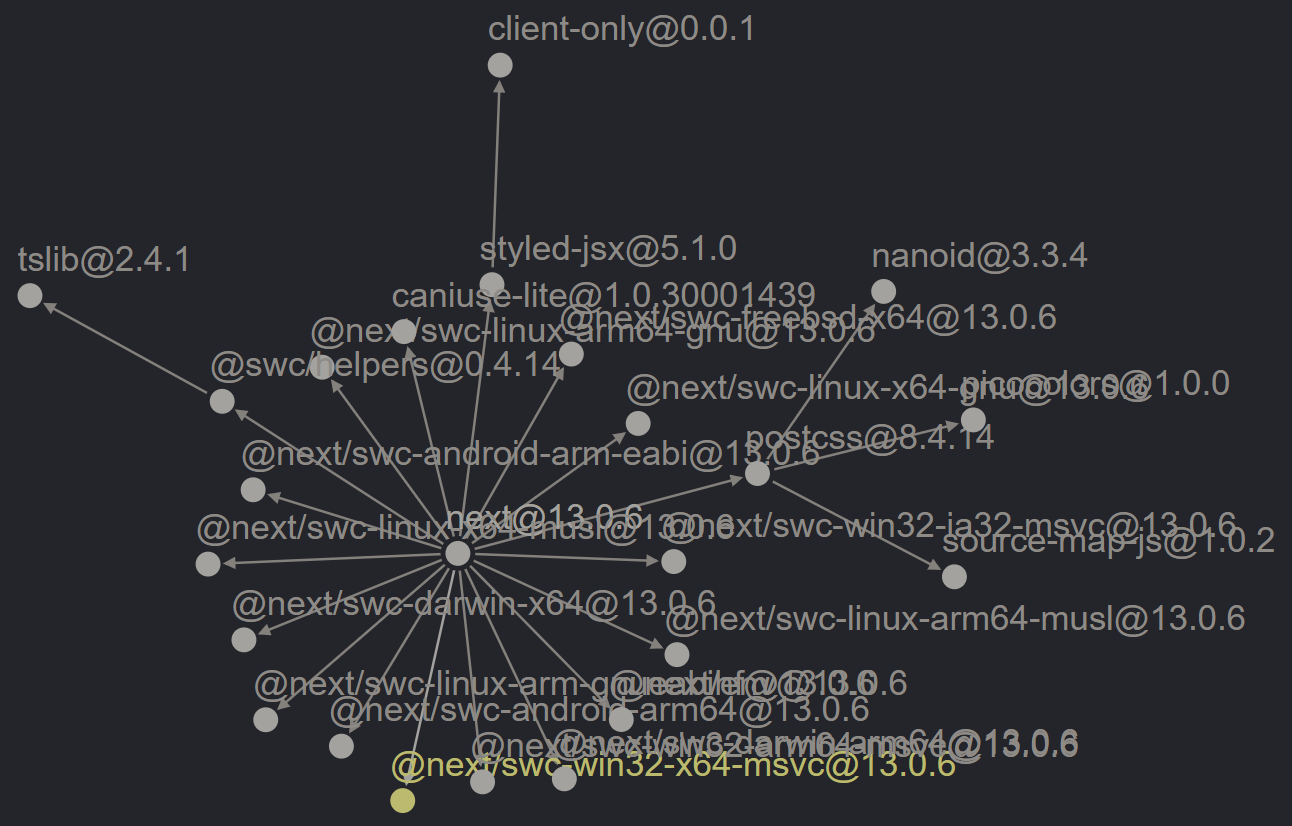

How entwined are dependencies these days? You can think of your project as a graph: each module represented as a point with declared dependencies as lines leading to other points. From your initial set of dependencies might sprawl out a veritable nest of lines, localized centers of activity, and even duplication. Maintainers that understand this often endeavor to decrease or remove dependencies from their offering. The less they have, the less they pass on to adopters. Frameworks, by their nature, bundle library functionality with conventions to create their value. But they too benefit from a reduction in dependencies. Let’s peek within the React ecosystem and compare Create React App86 with Next.js.87 The latest version of Create React App contains one thousand thirty-seven dependencies, (FIG 3.2)88 compared to twenty-three for Next.js. (FIG 3.3)89

FIG 3.2: Create React App’s “react-scripts” dependency tree visualized—one thousand thirty-seven dependencies in total.

FIG 3.3: The next framework dependency tree visualized—twenty-three dependencies in total.

Earlier versions of Next.js had hundreds more—so a concerted effort was made to internalize and reduce dependencies. Next.js’s internalization comes with a compromise, however. The more secure, stable bundling translates to larger binaries. These projects offer similar functionality with vastly different dependency postures. You can imagine what could go wrong with so many pieces of software crammed together like a clowncar.

If you are having trouble imagining, we don’t need to look too far. These dependency relationships create wobbly block towers. Sometimes they fall over spectacularly, without warning, and cause a great deal of noise.

- The PostCSS ecosystem deleted a file during a patch release. This brought down dependent tooling, such as Create React App.90

- Another accident occurred within is-promise, when the maintainer switched bundling conventions without understanding that it would alter import / export mechanics.91

- The Nx monorepo management tool released a minor update that removed its own bundled dependencies, omitting an automated migration to add them back into user systems.92

Events like this are more common than I’d like to admit, but then they are over. Usually the problem is discovered quickly, and a fix pushed in a matter of minutes or hours. This is open source Jenga, the tower toppling over. We all agree to pick up the pieces. Despite the annoyance, when things fall over, the community corrects.

More concerning is when developers understand how fragile our dependency foundation is and seek to weaponize or exploit it. The infamous left-pad incident93 affected projects the world over when its maintainer in protest unpublished every npm package they controlled. Missing dependencies caused thousands of cascading failures as dependent projects looked in vain for the library. The incident and aftermath led to improvements by the npm registry to prevent this in the future. It also highlighted again the compromise developers make when taking in dependencies—the left-pad algorithm isn’t novel or intensive to write (in fact now included in JavaScript as padStart), but it’s still possible to offload it to someone else. The Faker and colors libraries were similarly hit with intentional sabotage,94 their maintainer citing unsustainable funding models. Targeted sabotage emerged as a form of protest after Russia illegally invaded Ukraine too.95 Worse yet are malicious actors publishing packages intended to ensnare unsuspecting users, either through typo-squatting,96 account takeover, or dependency confusion.97

These risks strain the open source contracts we work within. Luckily, we can take steps as consumers and maintainers to safeguard our code. The dependencies your project uses (or doesn’t use) are just as important as your first-party code. Exercising prudence in adding new dependencies will always pay off. Know when to dial up the scrutiny. Be excited that someone else has solved that problem for you, but make clear accounting of the tradeoffs you tally in taking a dependency.

Do I Even Need a Dependency?

I’ve been talking about dependencies as if their inclusion in a project is a near-forgone conclusion. The open source landscape creates this illusory abundance for us. But know that there is always a choice, that near-hidden value exchange we engage in as consumers. We can choose to not take a dependency and therefore retain utmost control. The aged but still relevant You Might Not Need JQuery98 and You Might Not Need JS99 sites are testament to the options before us and the trade-offs we make.

We constantly delegate complexity out of our minds or adopt shortcuts to focus on what matters more. This is true for getting coffee as it is choosing a date library. We interact with these complex ideas via neat, well-defined APIs. But there is choice to be had in the APIs we integrate. driveToStarbucks() is an opposing implementation to brewPot(), though the output of caffeine is the same. Why? The cost and carbon footprint couldn’t be much more different—the value exchanges are imbalanced, (FIG 3.4)100 as are the page weights associated with too much JavaScript.

FIG 3.4: Abandoned mobile-order drinks at a Starbucks after they got reportedly an hour behind fulfillment. With “free” refunds, what’s the cost? Photo posted by LI0NHEARTLE0 on Reddit at https://www.reddit.com/r/pics/comments/yxu5e6/

Let’s analyze a theoretical dependency decision. Say you need to add a feature to a wedding website, counting down to the big day. As a UX enhancement, we want it to display a human readable amount of time, such as “in 5 months.” As the date gets closer, this will change to “in 17 days,” “in 1 day,” maybe even, “in 2 hours”. We have a lot of options at our disposal here.

You might reach to the popular Moment.js library to start. The moment(weddingDate).fromNow() function will accomplish this for us as a convenient and expressive one-liner.101 But the whole library comes for the ride, and if not optimized, takes a whopping 1.4 seconds to download on a slow 3G connection.102 We can do better. Admittedly, Moment’s maintainers agree (the library is deprecated).103

An alternative library exists, Day.js, ninety-six percent smaller, taking fifty-seven milliseconds on the same connection constraints.104 That’s twenty-five times faster. Except for when you want this relative time feature, then you need to load a plugin too.105 The composability is something you opt into, rather than getting the whole kitchen sink. That might be a good enough balance for most products. Have that conversation with your team—and as Dan Mall says, “decide in the browser.”106 Does it work on the device classes you care most about?

But further, we should wonder, could we write this code ourselves? Could we do it as efficiently as Day.js is doing it, while implementing forty-six assertions of accuracy via automated unit test?107 Perhaps the answer is yes, since our hero API the Intl.RelativeTimeFormat108 method makes this a native feature available to around ninety-five percent of devices globally.109

I wrote up my own version of this feature, working my way through encountered pitfalls as if I were writing it for a client or a product story.110 It wasn’t hard, but it was nuanced.

- RelativeTimeFormat expects you to provide it the value as an integer and the unit of measure. So I first had to compare dates using epoch time, and then hold onto the difference between dates as milliseconds.

- For the unit of measure, I need to do some quick math to figure out what ballpark of time our timespan is. Are we talking years, months, days? Do we care about hours and minutes? I didn’t handle those, but a good implementation would.

- I decided the formatter should look forward in time and also backward in time, so the difference value timespan needed to be revisited to provide a positive or negative value to the API.

- The end result, minified and gzip encoded, measured two hundred ninety bytes.

As a one-off feature, perhaps this is adequate. And it should have test coverage in an ideal world. Recall the question, “where do you want to spend your time?” Consult your own analytics, use cases, and desired user experience to inform your decision.

Despite the standardization of RelativeTimeFormat making its way into browsers, Moment.js is the eleventh-most-used npm dependency according to the Linux Foundation / Harvard Census released March 2022.111 Its ubiquity might be a lagging indicator of project downloads, but the site npmtrends.com doesn’t indicate a decline even in the face of competitor growth.112 Why? Well, it’s easy to pick on a single use case like my wedding tracker feature and find a native solution—but can we so quickly match the breadth of Moment.js’s API? You might find yourself sweating the details of writing a date library instead of a wedding tracker. Maybe I should open source that, you say to yourself…

How Do I Evaluate a Dependency?

Stars, download counts, and the like only tell a story of consumption derivative of popularity. There is undoubtedly comfort and safety traveling in these herds, and we shouldn’t discard them as indicators. Ecosystem size has a large impact on availability of help, tutorials, and examples. I know a casual Robert Frost reader would disagree, but you will find more guidance and solutions along the well-traveled road than taking a chance on a low-visibility dependency.

Look to these alternative considerations if a deeper analysis of a dependency is needed. You might find a gem of a dependency on a dusty shelf, just waiting for a chance. Or you might disqualify a choice that at first seemed like a frontrunner. Identify the real risks to your project mitigated by the dependency. Look for net-win value exchanges.

API

Does the dependency do what you need it to? That feels like a safe place to start. Recall that the API is the public contract between consumer and creator. You want an API that is clear, stable, intuitive, and well-documented. Bonus points for:

- Types: this helps with editor code completion. TypeScript113 and JSDoc114 excel here.

- CommonJS and ES Module bundling: this helps with selective integration into your environment. CommonJS format is often associated with Node.js, while ESM applies to browsers and newer tooling.

- Versioned documentation: you’ll want an easy way to reference what once was, should you fall behind the latest release.

We need to go further than, “does it work?” however. Ask, “does it cause no harm?” An API’s efficacy and behavior should never be called into question. When we choose to rely on someone else’s code, the trust-fall exercise extends into our development environments, our CI systems, and more importantly our end users’ devices. The dependency should be as easy to remove as it was to add—lest lock-in or compromise creep into the codebase. Michelle Barker documents this struggle with Tailwind on her blog, CSS { In Real Life}115:

when evaluating the use of a dependency that has such a large reach within a project, it’s wise to also consider what happens when that dependency is no longer useful to us, or when a new release contains significant breaking changes that it might necessitate a large refactor to keep our project up to date.

If you think evaluating a dependency is a stressful task, know that it is nothing compared to the dread of feeling stuck within a specific technical path. Make sure your process drives the tools, not the other way around.

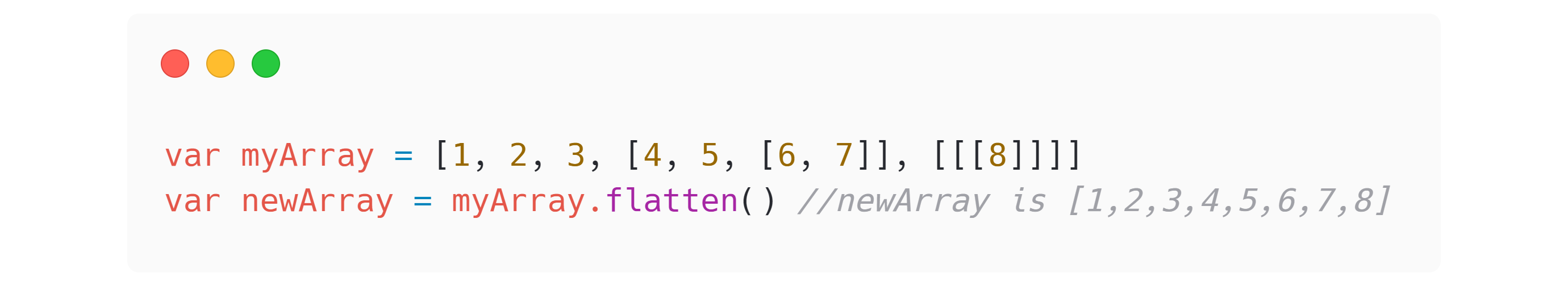

Perhaps the most famous API disaster of them all was “smooshgate”—a well-intentioned API decision so bad Google wrote a fifteen hundred word FAQ about it.116 The open source library MooTools117 established an array method called flatten which reduces an array with nested arrays into a single array. (FIG 3.5)

FIG 3.5: Demo of what the MooTools flatten method does to a complex array.

This sounds useful enough. So useful, in fact, that it was proposed118 as an addition to the ECMAScript 2019 specification (the standard defining how JavaScript works).119 When early previews of the spec landed in browser nightly builds, however, long-stable websites started breaking. Why? For some eight-plus years, Mootools implemented flatten (and many other methods) by directly adding to global Object prototypes like Array. This alters all subsequent instances of the object, leaking a proprietary implementation atop the standard. A long tail of old versions of Mootools were out in the wild, unmaintained, included on websites and CMSs, etc.. It was impossible to substantively address what would have been ecosystem-level instability. End users would suffer, running against the ethos of “don’t break the Web” that enable us all to still enjoy the first website,120 or the Space Jam homepage from 1996.121

But why the smoosh in smooshgate?

A contributor to the spec named Michael Ficarra proposed the rename from flatten to smoosh122 as a light-hearted solution. In the end, the proposal landed on flat instead of flatten (or smoosh). When your API choices impact the very evolution of the programming language, you’ve reached record-levels of engagement and value exchange (but not in the good way). It’s fun to jest in hindsight, but we still aren’t past these basic concerns. The React library is “instrumenting” the global fetch function under certain circumstances.123 What could go wrong?

Michelle Barker gives us this final gift about API scrutiny, from the same post as earlier:

By comparison, web standards evolve relatively slowly. But they evolve slowly for a reason: features that are added now need to be supported forever. They are not designed to become obsolete.

License

The open source license a project adopts cannot be understated. Permissive or restrictive licensing models prohibit or secure certain rights when distributing software. They are value exchanges that went to law school. You don’t want to be near or past the finish line on a release only to realize you are in noncompliance with a license. Determining the license of a dependency is usually straightforward, but there are a couple different places to check:

- A LICENSE file at the root of the repository

- A license key within the package.json file

- The README

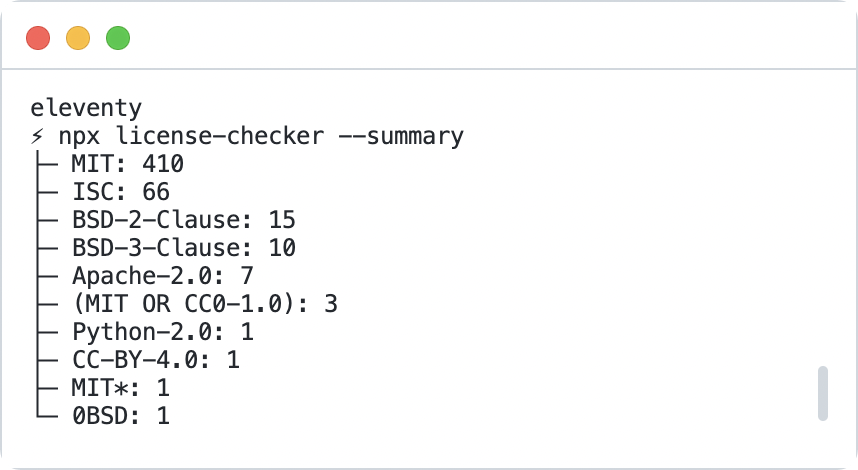

The lack of a standard can confuse tooling designed to determine compliance, so you need to be thorough in your search. For example, npm view will only return values defined within package.json. A tool called license-checker124 will crawl your project’s node_modules directory and use a heuristic process (guessing) to find the license of each dependency. This can be useful for a broader review of the code comprising your work, not just inspecting a single dependency. (FIG 3.6) You can filter certain licenses, direct output to different formats like json or csv, or fail the command outright on the discovery of specified licenses.

FIG 3.6: license-checker output for the Eleventy project. The tool deeply inspects all dependencies and reports the license groupings and counts.

Some licenses like the GPL125 require you to disclose the source code of any distributed work relying on it. Being cognizant of the licenses laid as the bedrock of your project’s dependencies is an important determinant of its own capabilities, liabilities, and perhaps marketability. Who maintains and governs the license is important too. The gold standard is a project governed by an open source foundation. Be more wary of the single company or single individual projects—their motivations might shift out from under you. You don’t want licensing to be an afterthought with an angry engineering manager, legal counsel, or client. We’ll cover this topic more fully in Chapter 4 too.

Longevity

The age of a dependency says a lot about its resilience or adaptability to changing trends in the marketplace. A flash-in-the-pan technique or now-fallen-out-of-favor approach both present as fleeting sizzle. But a project like the Express web server,126 for instance, has a slow-burn staying power that is evident in its fifteen-plus year history. Competitors arrive to usurp Express, even from its own creators, but none have dented Express’s pervasiveness. Which is weird when you look at their analytics—it seems like the pace of development has slowed to a crawl. I’ve had the thought: is Express dead? Turns out that when an API is mature enough it doesn’t need more enhancement—there just isn’t much more room to grow without changing the intent of the module. In some ways, Express isn’t dead as much as it is done, a testament to its value and relevance. Look for dependencies that have seen and survived a few hype cycles.

Stability of Release

When evaluating a dependency, check its CHANGELOG or releases page. A steady, high-frequency of release is almost always a hallmark of a well-run project. Automatic merge and release strategies will generate a lot of activity, sure, but be on the lookout for something rotten with all the releases: regressions, botched artifacts, and costly cleanup.

Careful and considerate maintainers will take steps to ensure the stability of their toolset, shielding the community from unexpected change. This is the essence of semver-compliance, which we’ll talk more about in a bit here. Look for patches that contradict previous releases, or issues that mention a breaking change on a non-major release. I’ve mentioned now a few times “the speed of open source” and again here it’s like a skateboard on a hill. There is fun and fast and then there is out-of-control danger.

Community Safety

Download counts and vanity metrics won’t tell you the complete story whether a project is safe to use, either in the code or at the watercooler. Your favorite library may have a vocal minority of toxic fanboys eager to take one person’s preference as an affront to theirs. Remind them: it’s okay to like different things! Ask around. Check hashtags on social media, industry blog comment sections, and issue logs. See what folks gravitate to the community created by the dependency. Actions speak louder than words here. Does the project have an enforceable code of conduct? Are maintainers role models in setting the mood? Does it have inclusive representation worthy of your time? Can you envision engaging without flinching at the thought of responses? We hope to find projects that can meet our measure. And once we do, we need to be mindful consumers.

Responsible Consumption Habits

The dependencies we take onto a project must be managed sustainably. They are like any other tool we must acquire and organize, be trained on and teach, secure and extend to our will. They cannot rust from disuse, nor crowd out the workspace. The wrong tool applied liberally can complicate timelines and endanger the final product. You’ll know this if you’ve ever tried killing a fly with a hammer. We now have a more nuanced view of when we need a dependency and how to evaluate which one is right for us. How can we ensure our carefully considered open source dependencies remain under control?

Semantic Versioning

One of the principal ways we can keep dependencies in check is to thoroughly and rigidly follow semantic versioning, or semver.127 I’ve used the term a couple times already, so it’s worth level-setting now.

Semantic versioning within your project will most likely manifest within Git tags or the package.json file. Dependencies of your project will be defined in the latter, with any number of named modules accompanied by a version. The version can follow a couple different conventions, but most look like this:

MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH

1.3.4

This semver is a promise that the 1.X line of releases will always have a compatible API with one another. It’s a value exchange made numeric. If the promise is upheld by maintainers, upgrade the MINOR or PATCH version as your needs dictate—but exercise caution when upgrading the MAJOR. Look for changelog entries, release notes, and migration guidelines that help you navigate the changeset.

Semver helps you understand how change is introduced into your codebase. Whenever I field support questions, the first thing I establish either from questioning or commit analysis is, “what’s changed recently?” Many times an update to one or more dependencies is a culprit. Dependencies that do not follow semver should be viewed with scrutiny, suspicion, and reluctance. Unfortunately, you may not know the stove is hot until you get burned once. Then, you start to look for the signs of a healthy project. Incrementing semver releases. No hedging or wordsmithing about breaking changes announced in smaller versions. No complaints in an issue log of unintended behavior on upgrade. Semver is just a number—maintainers shouldn’t hesitate to communicate via its changing. The consistency and adherence to these concepts is as important as traffic lights are to the safe passage of vehicles. If one person breaks the rules, they may cause harm to themselves or others.

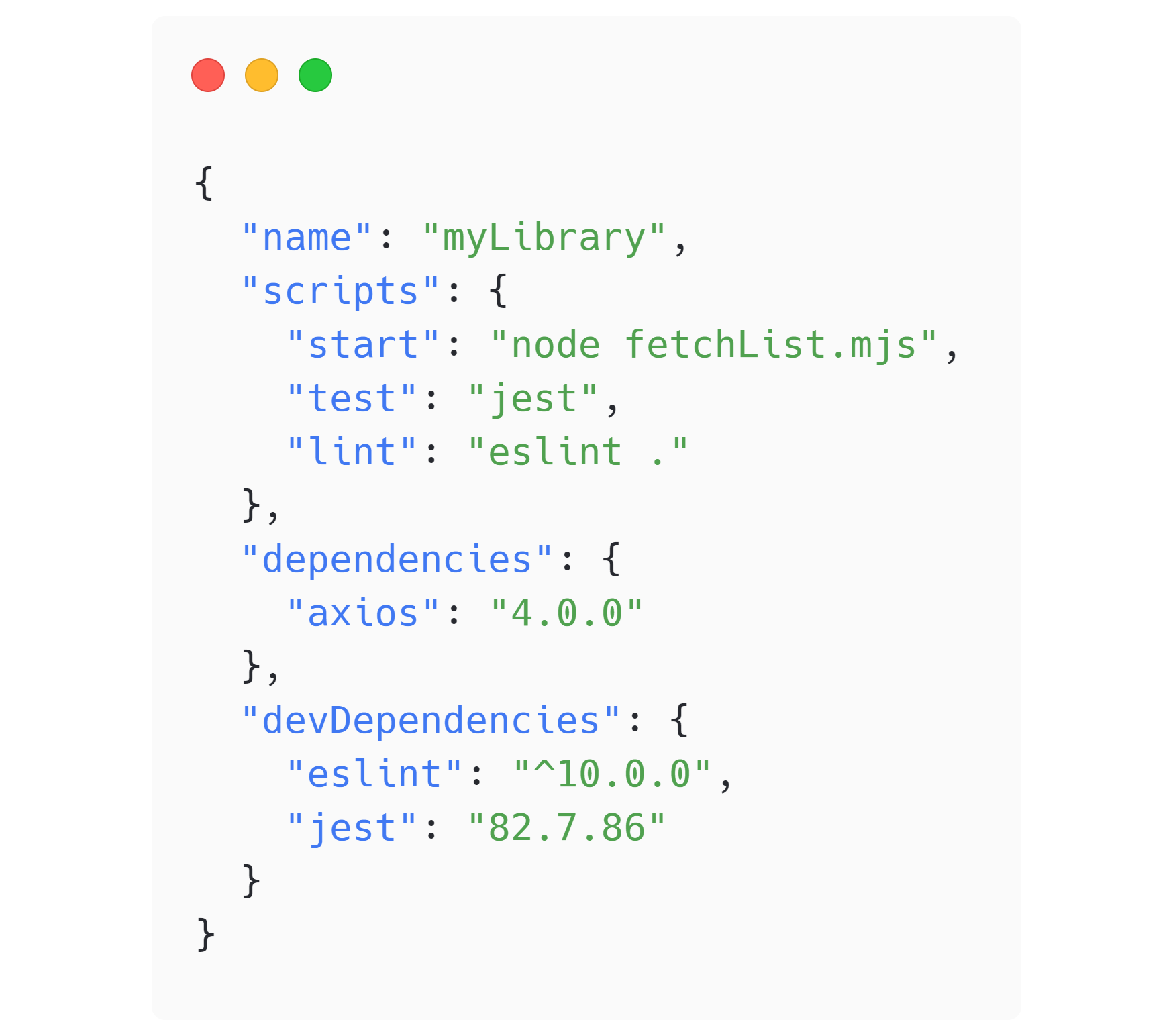

Our tooling assumes that maintainers follow semver. The package.json file describes the tools, dependencies, and configuration of most modern front end projects. It’s the recipe or owner’s manual you turn to when orienting to a new environment. We’ll use this package.json file as an example. (FIG 3.7)

FIG 3.7: A fictitious package.json with a precariously careted devDependency on eslint. A lockfile is the only thing keeping that declaration deterministic.

You might recognize our fetchList file from before. The code requires the Axios library to run, so we define that within the dependencies key (all at currently fictional values). The testing library we used, Jest, is still there too, but defined within devDependencies because it’s only used for local development and not distributed to consumers if myLibrary is published. Notice the code quality tool ESLint as the most notable addition. To get all these tools to run locally, you typically run npm install (and variants you can explore).

What Happens During npm install?

When npm install128 runs, the contents of the project’s package.json are read. The algorithm looks for dependencies to download and install. Every dependency is checked for dependencies itself, recursively, until a tree is formed of all project requirements. If a lockfile is present in your project, it is used to resolve this tree faster. Think of a lockfile as a pre-cached tree of dependencies. Sharing the lockfile with your team via Git makes everyone and your build server use the same deterministic set of dependencies too. Either way, the resolved dependencies are downloaded and installed in the node_modules directory, their optional bin scripts made available to the project. The lockfile is updated if dependency definitions or versions were altered in some way. You can configure a project to error during install if the lockfile and package.json dependencies get out of sync. Variant package managers like Yarn or pnpm have their own flavors of this algorithm. pnpm in particular goes steps further than npm in isolating modules from one another, and creating a local cache of downloads. Once downloaded and installed, dependencies are available for use within your project.

Semver-compliant Algorithms

Why the crash course on npm install? Well, because it gets more complicated. Built into semver and the npm installation algorithm are some conventions enabling developers to define version ranges. The two we highlight are the tilde(~) and the caret(^). The tilde matches MAJOR and MINOR versions, while the caret matches MAJOR versions. Absent a lockfile, these ranges allow npm to inspect each dependency’s published versions and pick the latest release that satisfies the range. For example, if eslint is defined within the package.json devDependencies section as “eslint“: “^10.0.0″, we are stating that any version of eslint greater than or equal to 10.0.0 but less than 11.0.0 is acceptable. You might want to do this if you trust the semver compliance of a dependent project. You are opting in to automatic bug fixes and non-breaking enhancements. Powerful. Useful. Dangerous.

Nevermind All That, Pin Your Dependencies

Why dangerous? This semver stuff doesn’t seem like a MAJOR deal. But, I suggest, that any project of sufficient size, team, and complexity will run into dependency management issues. It is inevitable, despite our best intentions. What could happen?

- Merge conflicts

- Local installation hiccups

- Major dependency upgrades

- Surgical lockfile-only patching of transient dependencies via security tooling

- Inconsistent install methods

- Switching branches

Each one of these mundane events increases the likelihood that a developer will want to blow away their lockfile. They will do it, because it’s an easy troubleshooting step and feels safe to do when panic strikes. The text scrolls by fast and they feel in control. But when they do that and re-run npm install, the resolution and installation algorithms run again with no project-level context. Suddenly the “eslint”: “^10.0.0″ version that was resolved and locked to 10.1.1 a moment ago has upgraded you to 10.6.0 complete with new lint rules that break your CI system. It’s a subtle and simple way to bork up your day.

The determinism of a lockfile can extend further into the dependency tree, into transient dependencies too, so there is value in checking a lockfile into Git and attempting to keep it in sync. Yet I’ve even seen teams git ignore their lockfiles. We should go a step further and always “pin” our dependencies to explicit versions within the package.json. Pinning removes the caret or tilde characters that are establishing a semver range. If your project has an .npmrc config file129 at the root, adding save-exact=true will automatically make pinned dependencies anytime a new dependency is installed. It’s a measure better, and an important one. Pinning isn’t limited to npm-based projects either. For example, Rafael Gonzaga shows why GitHub Actions should be pinned by commit hash.130

Beware the Zero Dot Release

Exhaust other options before adopting a 0.X.Y release of any software—this is not stable and could change at any time. The default npm project initialization used to be 0.1.0—which always felt like a curious choice because it suggested uncertainty within API intent at the outset of a project. While that is likely true, I feel like it’s led to some high-profile examples of successful projects amassing huge adoption while not communicating properly with semver when they reach a threshold of functionality most would consider “general availability.” Simply put: people are using unstable code and no one minds.

A notable example was axios131 (until it released its 1.0.0 version in October of 2022), which incremented for years all the way to 0.28.1, each new release a potential quagmire to navigate. The fact that this library attracted tens of millions of weekly downloads with this release posture might be the largest collective fingers-crossed moment in the JavaScript ecosystem. Zero dot maintainers are either intentionally communicating risk (ok), are ill-informed of the trade-offs (sigh), or are willful in the lopsided value exchange they are setting up (yikes). Open source is like that though; some projects will go their own way, and we can choose to engage or vote with our feet. Even when traffic lights contradict the norms, the traffic flows nonetheless.

Dependency Management Tools

With such an overabundance of npm dependencies at our disposal, the ecosystem has built tools to cope, lest it collapse in on itself. Luckily, automation can help us keep up. GitHub’s Dependabot, for example, will tell you when a dependency is out of date or vulnerable, and even submit a patch for you. With any tool, however, misuse and circumstance can combine for negative consequences. Many security vulnerabilities reported in dependencies are unexploitable in practice and impossible to remediate, a potent combination of boy-cried-wolf seriousness. This always-alert posture is exhausting and unsustainable—fatigue will make you complacent over time. I suggest tuning any automated tool to reduce noise:

- Inform and act upon HIGH or CRITICAL vulnerabilities. Handle lower severities during an established cadence of maintenance.

- Batch and schedule automated updates so you can plan for their review.

- Invest in more robust testing coverage to ensure automated updates are safe to integrate.

- Be wary of updates that only impact a lockfile—they will regress with any lockfile deletion.

There’s still plenty to celebrate in this space. That such deep insight exists into these complex ecosystems is exciting. Many tools have broad language support now too, offering scopes beyond npm into Docker images, Node.js versions, Ruby, Java, Go, etc. See the Resources at the end of the book for some specific tools I’ve found useful.

No matter the tool, periodic dependency updates you can set your watch to position your project for the most success. Monthly or quarterly updates seem to occupy a sweet-spot balance regarding a cadence. Wait too long and public documentation may drift. It’s distracting and noisy to update all dependencies all the time, so use your discretion regarding severity, effort, risk, and impact. Critical bugs should be patched faster, but in general, a slightly longer timeline can help smooth out unstable release thrashing. Allowing dependency debt to spiral out of control is detrimental to project security and individual productivity.

It Depends

There is an app for everything, and increasingly, an open source offering to compete with it. Whether you turn to a standalone program or the codebase you compose together, open source consumption affects you. It is often said that software is eating the world. Almost as many folks are now saying that open source is eating the industry even faster. André “Staltz” Medeiros coined the metric “time to open source alternative” and observed that it appears to be decreasing. (FIG 3.8)132

FIG 3.8: A graph showing a decreasing “time till open source alternative” for proprietary software. Image copyright Andre “Staltz” Medeiros is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The proprietary monopoly of yesterday is gone. The explosion of choice overwhelms the mind and can bring about analysis paralysis if you are not careful. Our landscape is every day more open, more inclusive, and more navigable, while also becoming more complicated, fragmented, and perhaps insecure due to its size and complexity. Can you trust anyone or anything far enough to come to rely on them? Will it be around tomorrow? Next week? Next year?

And yet it’s clear from nearly every professional and personal experience: we depend on one another. The family needs the grocer who needs the co-op gardeners who need the farmer who needs the machinist. It’s a lie to think otherwise. Projects depend on one another. Systems depend on one another. Economies depend on one another. We cannot escape interconnectivity.

This interconnectivity is a gift and a burden. We are delighted in the shortcut, the serendipity, and the solution solved faster. The vulnerability we open ourselves up to when engaging and depending on relationships is what makes it special. And it is risky. If we are fortunate and discerning, we can choose the degrees of quality in these relationships and abstractions. Which yields better results? I said before this is a false dichotomy, a strawman argument. Don’t fall for it. Instead, seek the value exchange beneficial to the moment. Seek the dialog about what’s right for the project now, and into the future. It’s tempting to repeat the programming joke, “it depends.” And I think you’d be right in the declarative sense.

So let’s embrace dependency when we need to, with careful craftsmanship. Let’s with intention engage. If and when the time is right, you’ll find that thing you want to open source. Who knows, one day we may depend on you.