Toward the end of a recent post, “Do I Need This Node Dependency?”, I proposed the notion that the perceived turmoil and change in the ecosystem was actually a sign of vibrancy.

🎥 Watch the talk I gave at JSConf 2025 where I explain this idea further.

I want to dedicate discrete space to explore this idea further. As I said there, “if I wrote Approachable Open Source today, I’d be talking bout this.”

Pace Layers and Symmathesy

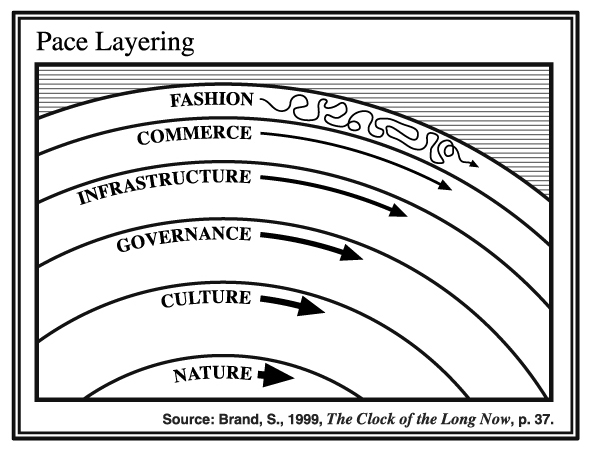

Stewart Brand’s 2018 paper, Pace Layering: How Complex Systems Learn and Keep Learning, has taken hold in my thinking of late. Therein he models all of civilization against a backdrop of concentric layers of time, or change. At the core we have truly glacial timelines, nature itself forming the bedrock of our existence. Higher up we get into societal structures, thought frameworks, generational investments, competition, and experimentation. Each change we see is a story in and of itself, but together they form a narrative. A narrative of complex, mutual learning.

The best ideas put pressure on the established systems around and below them. Sometimes a new idea is so radical that it shakes up the whole system: perhaps the printing press, or fossil fuels, or AI. The point being, these layers exist in relationship with one another, and individually exhibit their own depth, characteristics, constraints, and mechanisms.

What clicked for me was conceptualizing pace layers in relation to symmathesy, or mutual learning in living systems. Recall: Nora Bateson coined this term: latin for “learning together.”

These two concepts are great in isolation, pace layering is a way to diagram symmathesies.

I can see Node.js somewhere in these deeper layers, a foundational project with gravity. It simply cannot move as fast as competitors, or libraries built to augment it. That’s okay. We can witness things like Deno and Bun putting pressure on Node.js. Not directly (or perhaps so), but through the ideas they explore, the features they introduce, and the expectations they raise. The best of these ideas, or the most common use cases in userland, seem to find their way into the standard library.

This is an obvious echo to a concept I first saw from Jeremy Keith’s The State of the Web (Video, Transcript). He describes how web platform features often start as polyfills, then move to libraries, then frameworks, and finally are absorbed into the platform itself. This is pace layering in action. Examples cited include jQuery, Sass, maybe even Flash. Now we see this with Node.js. My talk, Lizz Parody’s post: 15 Recent Node.js Features that Replace Popular npm Packages, all suggest this dynamic.

What’s cool too, is that a lot of these Node.js features were landed in consultation with the maintainers of the dependencies they might disrupt. This is commendable, healthy, mature behavior and the opposite of the chaos often lampooned or derided in the open source community.

🔥 When you get frustrated at the churn of any ecosystem, try to frame your perspective in these pace layers. We are all at once viewing, consuming, and contributing to systems moving at different timescales.

Open Source Pace Layers

Some tools feel seismic in their progress, foundational to how we do things. Think Linux, curl, or specifications. Some work moves at a faster rate, collectively learning from and iterating on the layers below it, exploring the adjacent possible. The best ideas put pressure on the established systems, where they are absorbed, systematized, and made more stable. Open source as a Law of Nature here helps prop up and propel the vibrancy of the system.

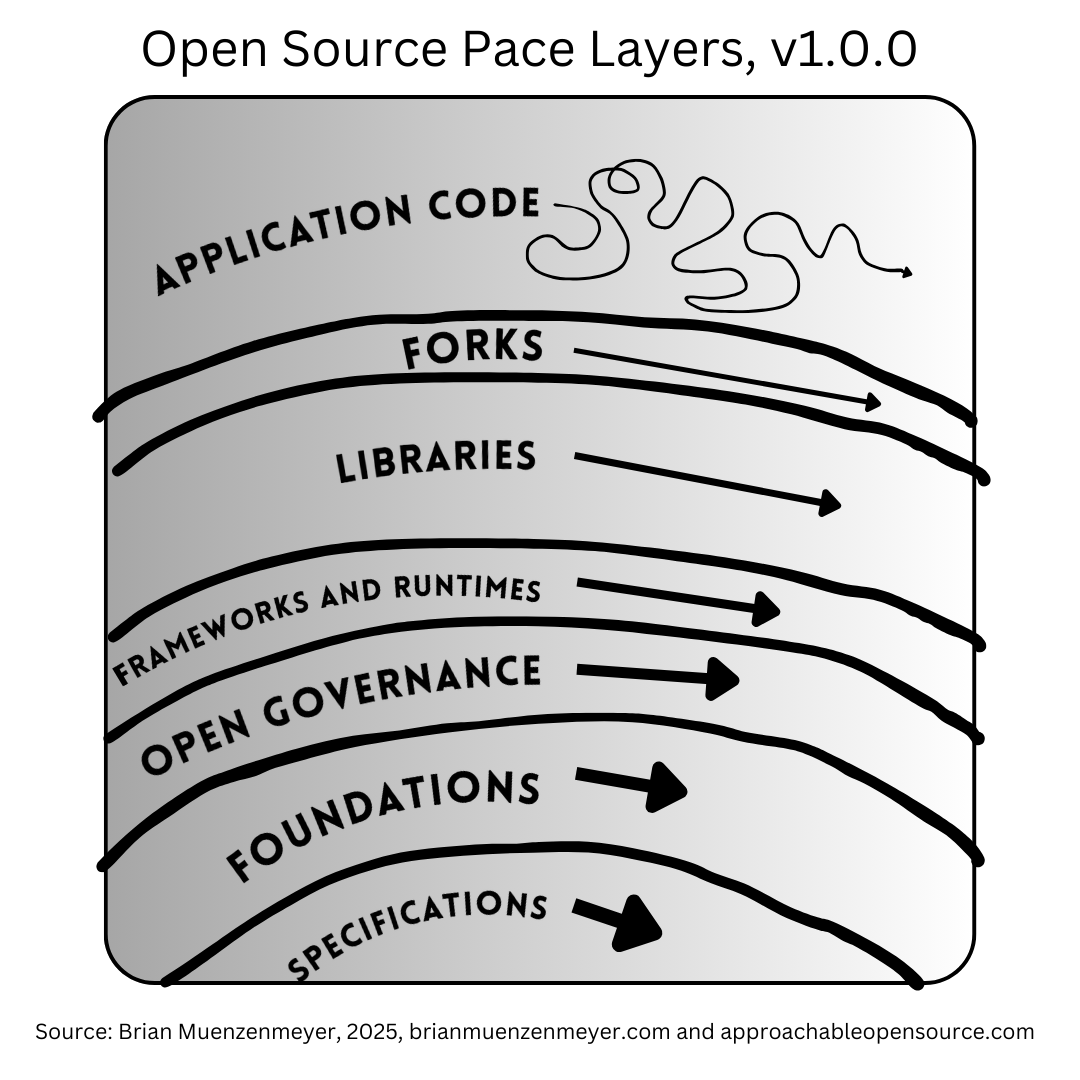

Here’s an early diagram of my Open Source Pace Layers (drawn at 2AM forgive me):

Highest I place our application code: the unique inventions we create to solve problems. No one is alike from the other, try as we might. Often they are a composite of lower levels. Nothing here is permanent. You might change that feature tomorrow. Are you writing code the same way you did five years ago? This is territory of AI coding assistants, well-equipped to augment, glue together, riff on, steal, remix, and ramble. I digress.

Below our application code we have forks: the first open source-y thing in our pace layering. Forks are disruptive, intentional statements of intent. Or they are fleeting methods to contribute upstream code. Either way, they are easy to create, but likely short-lived. The best positioned supplant their hosts.

Libraries occupy the next layer, and I’ve intentionally made it the largest. Brand’s pace layers suggest a gradual size increase as we move inward. I’ve introduced a bit of nuance against that here. Libraries, like functions, form the building blocks of our DRY (don’t repeat yourself) perspective as technologists. They are the sweet-spot fidelity for purpose-built tools. The Unix philosophy of doing one thing well applies here. Their size and portability support forks above and composites below.

So naturally next we have frameworks and runtimes: opinionated collections of libraries and conventions. By definition they have larger scope and influence over how we build. This can help and hinder. If we go “with the grain” of a framework, we can move quickly. If we fight it, we might be in for a rough time. These tools also risk lock-in as their footprints and ecosystems grow. The cost to change is high because the impact is equally so.

Below that I place open governance: projects with formalized decision making, charters, procedures, teams, enforcement mechanisms, and escalation paths. This is a concept interjected between more clear nouns, but I believe this is a notable gradation. Openly governed projects move slower, but with less risk of sudden change. Less relicenses, rugpulls, monetization pivots, or abandonment. Less VC funding influencing direction. The projects that are openly governed tend to stick around.

Deeper still are foundations: neutral stewards of entire ecosystems. Advocates for collaboration and sustainability beyond the budget of any single company or character. Organizations with resiliency built in as a core principle: meant to nurture and grow the entire movement within their means. This work is diplomatic, strategic, partnering at the highest level. They might be the arbiter of rivals, the conduit for funding, and the home for projects of all flags and flavors.

At the core we see specifications: the standards and protocols and their communities that form our shared understanding. These are deliberate, and seek consensus on timescales measured in years if not decades. Specifications spur implementation and innovation above them, often along that pathway Jeremy Keith described. From idea to spec to polyfill to library to standard.

Find Your Layer

This is all a great setup for Chapter Two: The Spectrum of Engagement. In the print version of the book, we save some of the heaviest theoretical why bother with open source? for later chapters. But symmathesy and pace layers here really tease the notion that successful open source projects and ecosystems require contributions across many roles. The work will vary with maturity, but it’s all complementary within a larger living system.

So, via chaos and happenstance by design, we can celebrate that:

- innovation can be quick / creators have agency to explore

- competition puts pressure on established systems to improve

- maintainers craving inertia and stability have space and time to cultivate

- layers exist for anyone to contribute within their means

tl;dr: There’s space for you within open source. I promise.

Watch the Talk

I synchronously explained these concepts recently at JSConf 2025. We start with a bunch of examples from Node.js adopting userland features, and then close with our unifying theory of movement. Check it out! 👇 🎥